Bal Gangadhar Tilak was well known as an extremist and revolutionary. By limiting him to these terms, historians misjudged him with a bias towards Anglo-saxan supremacy and left different facets of Tilak unexplored.

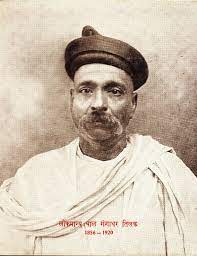

Bal Gangadhar Tilak, popularly known as Lokmanya Tilak has been referred to as ‘the father of Indian unrest’. He has often been interpreted and largely misinterpreted as a revolutionary, an extremist, and a nationalist leader who supported the use of violence. Historians, both British and Indian have classified Indian leaders into water-tight compartments of “liberal” and “conservative” (implying orthodox); it is no surprise then that Tilak has been forced into the box of conservatism. It is imperative to understand the reasons behind this misinterpretation of Tilak – what A.B Shah terms as ‘miscarriage of historical scholarship’[1].

According to Shah, while studying Tilak and his ideas, Indian historians have judged Tilak entirely according to the norms of the Gandhian age. Their scholarship fails to recognise that M.K Gandhi’s ideas were a product of the dialectic between the previous generation of Indian leaders like Tilak, Gokhale, Bipin Chandra Pal, Sir Rashbehari Ghosh among many others. Secondly, Indian historians have favoured British sources over vernacular Indian sources. It is implicit that the sources of an imperial government, of racist writers and journalists, cannot do much justice to Tilak[2]. Indian scholarship has comfortably relied on writers like Valentine Chirol who were instructed by their belief in the white man’s burden and in Anglo-Saxon supremacy. The introduction to Chirol’s book written by Sir Alfred C. Lyall reveals the larger attitudes held by such writers. Lyall writes, “Chirol’s whole narrative illustrates the perils that beset a government which finds its own principles perverted against its efforts, and its foremost opponents among the class that has been the first to profit” (Lyall, 1910, viii). It is interesting to note that the repressive measures of the imperial government have been touted as liberal principles and the opposition to such repression has been criticised. The idea of European supremacy is voiced unambiguously as Lyall writes, “In India, the eighteenth century was a period of abnormal and extensive political confusion. In Europe, on the other hand, national wealth, scientific discoveries, the arts of war and peace, had made extraordinary progress” (Lyall, 1910, ix). While commenting on the possibility of democracy in India, Chirol states unequivocally, “There was and is no room for Parliament in India, because, so long as British rule remains a reality, the Government of India, as Lord Morley has plainly stated, must be an autocracy – benevolent and full of sympathy with Indian ideas, but still an autocracy” (Chirol, 1910, 154). How a “benevolent” autocracy is compatible with the liberal British political system must be best known to Valentine Chirol. The ideas of leaders like Tilak come to be distorted when seen through the lens of writers like Chirol.

The purpose of this article is to bring to light the liberal nuances of Tilak’s ideas which challenge the labels attributed to him. The Age of Consent controversy of 1891 is routinely used to paint Tilak as a parochial traditionalist. However, a closer look at Tilak’s position reveals that Tilak was not opposed to increasing the age of consent from 10 to 12 years of age for girls. Tilak’s opposition was not against social reform but against state intervention. Tilak believed that an alien government, the state, had no right to meddle in the affairs of a community, however beneficial the meddling may be. He reiterated the liberal principle that law must be derived from the practices, beliefs and traditions of the community; he suggested that the public opinion had to be shaped before enacting laws. What is often missed is that Tilak got his daughters Krushnabai, Durgamai, and Mathutai married only after they turned 12 years of age. While Tilak opposed the Age of Consent Bill, he believed in increasing the age of consent for girls, and he practised what he believed in. In contradiction to Tilak’s attitude of practising what he preached, several reformers within the Bombay presidency failed to practise what they preached. In October 1890, Tilak proposed a convention before the reformers who had gathered for a meeting. The convention stated that the reformers would not get their daughters married before they turned 12 years of age and that reformer men above the age of 40 would only marry widows. The convention also stated that those reformers who were found to violate these clauses would be fined. It is interesting to note that only Tilak, Agarkar, Bhandarkar and a few others signed the convention while most others refused to sign the convention[3].

As a leader from the Brahmin community, Tilak has been presented as a man who believed in caste hierarchy. Once again, the Indian historical scholarship falls short in understanding the true nature of Tilak’s ideas on caste. The ‘moderate’ leadership in the late 19th century included Gopal Krishna Gokhale, M.G Ranade, Dadabhai Naoroji, Pherozeshah Mehta, Sir Surendranath Bannerjee, Sir Rashbehari Ghosh among others. The moderate leadership was largely homogenous in their composition in the sense that all were English educated. The moderate leadership believed in prayers and petitions and sought to develop a dialogue with the British administration. The moderates believed in gatekeeping this dialogue for a few elite intellectuals (mostly from classes and castes that were considered as upper). Gokhale firmly believed that the ordinary citizens of the country must not become a part of the struggle against the imperial state (Pagdi, 2011). B. Pattabhisitaramiah suggests that Gokhale’s methods sought to win the foreigner, Tilak’s to replace him; Gokhale looked to the intelligentsia, Tilak to the masses; Gokhale’s arena was the Council Chamber, Tilak’s forum was the village mandap[4]. Tilak sought to give the national struggle a truly national character by involving people from all walks of life. Tilak was given the epithet ‘तेल्या – तांबोळ्यांचे पुढारी’ (telya-tambolyanche pudhari), meaning the leader of the working classes[5]. He spoke and wrote in favour of abolition of untouchability. Tilak spoke at the Conference on Abolition of Untouchability, held on 23-24 March 1918, and presided over by Sir Sayajirao Gaekwad. Tilak stated unequivocally, “If God were to tolerate untouchability, I would not recognise him as God at all” (Shah, 1983, 206).

Tilak has often been portrayed as a Hindu revivalist and as a leader who was dismissive of minorities. A thorough study of Tilak and his relation with his contemporaries, however, reveals a different truth. Tilak believed that the minorities, especially the Muslims must have an equal place in the local and national platforms for Swarajya. The accusation that Tilak alienated Muslims from the struggle against the imperial state is rightly challenged by his 1916 speech. At the Lucknow session in 1916, Tilak put up the proposition of changing the three-way fight among the British, the Hindus and the Muslims into a two-way fight where Hindus and Muslim would fight united against the imperial British state. Among Tilak’s close friends and admirers were Barrister Mohammed Ali Jinnah and Maulana Hasrat Mohani. When Tilak was charged with sedition in 1908, Barrister Jinnah quickly moved the bail application which eventually was rejected. The Lucknow pact signed between Tilak and Jinnah in 1916 was a sincere attempt at weaving a thread of unity between the Hindu and Muslim communities. When in Chindwara prison, Jinnah wrote to Tilak, “Your courage, resolution and fortitude are an example to us, younger men, whatever be our politics, and these have convinced me, that after going through all this, you could never contemplate with equanimity, much less desire, that even a particle of the same suffering should be inflicted on a fellow countryman, no matter of what caste or creed, equally in the defence of freedom and self-respect”[6]. Although Tilak was a staunch practising Hindu, “Tilak was free of communal bias and preferred to keep religious agenda out of politics” (Pagdi, 2011, 115). Maulana Hasrat Mohani was a strong supporter of Tilak[7]. In 1907, when Tilak walked out of the Congress party, Maulana left with him[8]. Maulana wrote a moving poem on the death of Tilak. He wrote :

Maatam ho na kyun Bharat mein bapa, duniya se sidhare aaj Tilak

Balwant Tilak, Maharaaj Tilak aazaadon ke sartaaj Tilak

Jab tak wo rahe duniya mein raha hum sab ke dilon par zor unka

Ab reh ke behisht mein nizde Khuda rooho’n par karenge raaj Tilak

(Why wouldn’t Bharat grieve, Tilak has left this world today.

Balwant Tilak, Maharaj Tilak, the pride of the free-spirited

Till he lived he ruled our hearts

Now that he’s with the maker, he will rule our souls)

The liberal nuances in Tilak’s thoughts and ideas are crystallised in his defence arguments when he was charged with sedition in 1908. Tilak’s central concern “was to publicly articulate the Indian people’s rejection of a law grounded in the primacy of colonial/ imperial power and not on popular sovereignty. Colonial law so far as it was not anchored in society, nation and community, Tilak publicly declared, was by its very nature, illegitimate” (Mukherjee, 2017, 4). Tilak defended not only his writings in Kesari but sought to defend the freedom of the native press in India. According to Gerald Barrier, more than two thousand Indian newspapers came to be censored by the British government between 1901 and 1947 (Barrier, 1974). Against the repressive measures taken against native press, Tilak asked the jury, “if the press in England had the right to criticise the bureaucracy and raise public opinion about the policies of the government in England, why should the press in India be denied the same rights?” (Mukherjee, 2017, 11) The British rule of law could interpret any word as seditious or libellous, and in such conditions, Tilak said, “you could only beg, not claim as a right. Political discussion could only be carried out on the sufferance of the government” (Kelkar, 1908, 175). Inevitable as it was, the imperial British judiciary convicted Tilak of sedition. His remarks on the pronouncement of his verdict are deeply reminiscent of Thomas More’s last words addressed to King Henry VIII[9]. Thomas More said before his execution, “I die the King’s good servant, but God’s first”. Tilak rejected the very legitimacy of the law which convicted him and yet accepted the consequences. “All I wish to state is that in spite of the verdict of the Jury I maintain that I am innocent. There are higher Powers that rule the destiny of things and it may be the will of Providence that the cause which I represent may prosper more by my suffering than by my remaining free” (Kelkar, 1908, Part 2).

Lokmanya Tilak is an amalgamation of a variety of political thoughts. A staunch believer in spirituality, Swarajya, and a man who vehemently opposed state intervention and British misrule, Lokmanya Tilak was a teacher, a writer, a journalist, and a national leader. He relentlessly exposed the hypocrisies and the fallacies of the British administration in India. He believed that those who were in awe of the colonisers could never put up a genuine fight to get rid of them; they could never concede the shortcomings of the imperial state and instead would keep pointing to the perceived progress the British brought to India. Tilak never publicly endorsed the use of violence but he was critical of the ‘moderate’ method of prayers, petitions and constitutional political movement. In an article in Kesari, titled, Sanadshir ka Kaydeshir (Constitutional or Legal), Tilak refuted the idea of constitutional movement saying, “Britain has not set any Charter of rights to Hindustan, therefore it would be ridiculous to say that the movement be conducted as per the Charter” (Pagdi, 2011, 96). Tilak was a man of many facets and an excessive focus on any one facet leads to an obfuscation of others, as has been the case with Indian scholarship. In Tilak, the conservative and the liberal intertwine imperceptibly. As A.B Shah says that Tilak was a conservative liberal and certainly not a revivalist as he is often painted.

Endnotes

[1] Shah, A. B. (1983). Tilak and secularism [Print]. In Political Thought and Leadership of Lokmanya Tilak (pp. 201–220). Concept.

[2] See Arthur Crawford’s Our Troubles in Poona and the Deccan (1897). Gayatri Pagdi refers to Crawford as ‘a man maddened by racism’ (2011).

[3] Find more in A.B Shah’s Tilak and Secularism (1983).

[4]Tilak and Gokhale : A Comparative Study, Mohammed Shabbir Khan, Ashish Publishing House, 1992. Qtd in Pagadi, 2011, 91.

[5] Tilak was a strong supporter of workers’ rights and he organised the workers to fight for the cause of boycott of foreign goods and Swadeshi initiatives. For more, refer to Pagdi, 2011, pp 199-214

[6] Inamdar, N. R. (Ed.). (1982). Political Thought and Leadership of Lokmanya Tilak [Print]. Concept.

[7] Qtd. in Pagadi, 2011, 116

[8] For more on Maulana Hasrat Mohani, see Jawed Naqvi’s piece in Dawn, 11 August 2010.

[9] Thomas More was an English judge, philosopher, bureaucrat and a humanist. He opposed King Henry VIII’s takeover of the church which in his view was a violation of secular principles. Along with many other dissidents, More was executed in 1535.

References

Barrier, N. G. (1974). Banned; Controversial Literature and Political control in British India, 1907-1947. [Columbia] : University of Missouri Press.

Chirol, V. (1910). Indian Unrest [Print]. Macmillan and Co. Limited.

Inamdar, N. R. (Ed.). (1982). Political Thought and Leadership of Lokmanya Tilak [Print]. Concept.

Kelkar, N. C. (Ed.). (1908). Full and Authentic Report of the Tilak Trial. Indu-Prakash Steam Press.

Lyall, A. C. (1910). Introduction [Print]. In Indian Unrest (pp. viii–xvi). Macmillan and Co. Limited.

Mukherjee, M. (2017). Sedition, Law, and the British Empire in India: The Trial of Tilak (1908). Law, Culture and the Humanities, 16(3), 454–476. https://doi.org/10.1177/1743872116685034

Pagdi, G. (2011). Lokmanya Tilak: The First National Leader [Print]. Indus Source Books.

Shah, A. B. (1983). Tilak and secularism [Print]. In Political Thought and Leadership of Lokmanya Tilak (pp. 201–220). Concept.