With the impending slowdown in the Indian economy, many analysts have wondered if Private Enterprise has failed in India. It is imperative to point out that since the 1950s the failures of Private Enterprises in India have been questioned. In this speech made before the Commerce Graduates’ Association in Bombay in October 1956, eminent industrialist, banker and economist A D Shroff points out that despite numerous impediments to growth Private Enterprise in India is alive and flourishing. His words remain as true today as they were in then.

For some time past, Private Enterprise in India has been continuously under fire. It has been suggested that Private Enterprise is incapable of undertaking large-scale and rapid economic development of the country. It is also suggested that Private Enterprise only results in the concentration of economic power in the hands of a few people. It is further said that-and it was said only a few days ago by no less a person than the Prime Minister of India in Calcutta-that Private Enterprise and Democracy are incompatible. But the main provocation for the choice of the subject is a speech made by Mr. T. T. Krishnamachari, who was then the Union Minister for Commerce and Industry, at Madurai on 4th of August. In the course of his speech, he observed that “Private Enterprise has failed me”, and that Private Enterprise was not showing either initiative or enterprise.

Before I proceed to examine the validity of the various contentions which have led some people to the conclusion that Private Enterprise has failed in this country, I should mention that of all Ministers of Industries since India attained independence, Mr. T. T. Krishnamachari must be acknowledged as an outstanding success. Some of us may differ from him on some of the views he holds and propagates. But I think there is not the slightest doubt that in the discharge of his very high responsibilities as the Minister for Industries, he has shown remarkable drive, energy and understanding of business problems, and above all a capacity for taking quick decisions. It is, therefore, all the more incomprehensible for me that a man of such fine understanding of business and industrial problems and a man who has first-hand opportunities of witnessing from day to day what was being done in the industrial sphere in the last few years, should have preferred to make this charge against Private Enterprise in this country. To quote a Shakespearean phrase, to me it has come as “the most unkindest cut of all”.

Before I examine the charge, it is very necessary that I should give you a brief historical review of Private Industry in this country, particularly before India attained Independence. If you look back to the history of Private Enterprise for 60 or 70 years before India attained independence, you must take into consideration the circumstances and the environment under which Private Industry had to struggle. For one thing, we were under a regime, which was quite indifferent and apathetic, if not in some cases definitely antagonistic, to any industrial development in the country. If you for instance study the Tariff Policy of those days, the Transport Policy, or the fixation of Railway freight, all these will show you the conditions under which Private Enterprise had to struggle. ‘Even in later years, when the Government came to adopt-and that too very grudgingly-a policy of discriminating protection, that policy was too halting and unsuited to bring about any rapid development of industries in the country. In spite of all these limitations and disabilities, Private Enterprise was subject to in those days, it was surely I through the enterprise and endeavour of Private Enterprise that India was put on the industrial map of the world and attained the eighth place among the industrial nations in the world.

To quote one or two instances; the Cotton Textile Industry (remember only about 40 years ago we used to import every year Rs. 60 crores worth of piece-goods from abroad) has now developed substantially in the last few years when we have become a very important exporter of cotton piece-goods to about 40 to 45 different markets in the world. The very fact that Indian piece-goods should effectively compete with shrewd and established exporters from Lancashire and Japan bears ample testimony to the efficiency with which Textile Industry has been built up in this country.

I would also like to remind you of the days when the late Mr. J. N. Tata first thought of starting the Steel Industry. I do not know if you are aware that a leading British businessman of Calcutta ridiculed the idea as a dream, and he even offered to consume every pound of steel made in India! Fortunately for him, he is not alive today; otherwise he would have suffered not a little from indigestion. But the fact of the matter is that a great pioneering effort succeeded in giving India the largest single individual steel-making unit in the British Commonwealth of Nations, and I believe India will be proud also of the fact that she is today one of the most economical and cheapest producers of steel in the world.

Take for instance also the development of hydroelectric power-entirely undertaken by Private Enterprise-a tremendous venture in those days, a venture not only in the sense of generating power but even of making Bombay millowners believe that power could be generated and supplied to Bombay mills. You know today what it stands for in the economic life of Bombay.

The above two or three instances might show what Private Enterprise, functioning under the limitations and disabilities to which it was subject in those days, could achieve. I may also mention Shipping. Shipping in India against the powerfully entrenched foreign shipping companies almost looked like a dream. It was due to the pioneering effort of the late Shri Narottam Morarji and Shri Walchand Hirachand that Indian Shipping has come to stay and offers today very fine promise of supplying a much-needed complementary transport service to sustain our economy.

Even before we attained Independence, in 1944 seven business men of India got together and put before the people a plan for the economic development of the country. The plan was sufficiently ambitious; it involved an estimated expenditure of Rs. 10,0001 crores over a period of 15 years and out of that it envisaged spending something like Rs. 4,4001 crores on development of Industries. I am mentioning this to show that Private Enterprise in India, even before Independence, was fully conscious of the needs of the country and also had faith in itself that it could undertake development on a very large and extensive scale. After 1947 the Government started taking more active interest in the economic development of the country. Private Enterprise also did not fail to assist in the process of development. The curve of industrial production during the last five years has been continuously rising. If you take 1946 as the base year, i.e., 100, industrial production went up to 117.2 in 1951, 128.9 in 1952, 135.3 in 1953, 146.6 in 1954, and in 1955 it stood at 161.5.

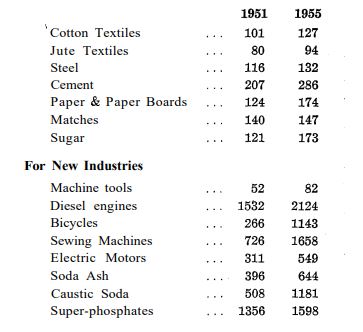

Let me make it clear that the overwhelming proportion of the increased production was contributed by Private Enterprise because the few State Enterprises which came into operation were mainly confined to the Sindri Fertilizer Factory, the Chittaranjan Locomotives, and the Indian Telephone Factory at Bangalore, etc. If you take the aggregate value of the production, contribution by the Public Sector represents a comparatively negligible percentage of the total. But the more interesting thing was this: if you break up the general index of industries and some of the new industries, taking 1946 as the base year representing 100, the increase has been for Old Industries:

This remarkable increase in industrial production during the past five years in which both old and new industries have equally participated and to which the State Enterprise has contributed comparatively very little ought to give a lie direct to the very charge that Private Enterprise has Failed to do its duty in this country. The index figures I have just read do not convey the whole story; besides this, important new industries were started, for instance Rayon. It was started and is prospering well and perhaps in the course of the next 3 to 5 years India will be self-sufficient in regard to requirements of Rayon yarn. Take again the Steel Tubes industry. Though this project was mooted even before the last war, owing to the exigencies of the War it could not be brought into operation. It has since been started and is one of the important industries in the country. Similarly, reference may be made to automobiles and trucks.

These are facts which of course cannot particularly be unknown to the Ministry of Commerce and Industry. They are there to tell their own story. But I would not like to quote anything which comes from private enterprise itself. Here is a statement made by the Planning Commission in a publication which is entitled “Progress of Industrial Development 1956-1961”:

“New investment on industries in the public sector during the First Plan was expected to amount to about Rs. 94 crores. The actual outlay according to the latest estimates has only been about Rs. 57 crores. Investment by the Private Sector on new projects and expansion programmes was expected to about Rs. 233 crores and the latest estimates indicate that the actual investment has been of this order.”

There is a body called the Industrial Finance Corporation of India-one of the few financial institutions which have come into existence after India attained independence. It has just published its 8th Annual Report in which it is stated that the total amount of loans sanctioned has risen from Rs. 9.5 crores in 1951 to Rs. 43.20 crores in 1956, and the number of applications for loans received have doubled from 43 to 86 during the course of the last 2 years. Further, from the office of the Registrar of Jt. Stock Companies, you will find that the number of joint stock companies registered and in actual operation have risen from 22,675 in 1947-48 to 29,779 in 1954-55.

You must be aware that one of the important new pieces of legislation after independence is the Industries (Development and Regulation) Act of 1951. Under this Act, you cannot put up a factory without obtaining a licence. According to the latest figures available, for 3 years up to 1955, out of 1,440 applications made to the Government for licences, 1,142 were granted. Of these, there were 363 licences for new schemes, 657 for expansion schemes and 122 for organisational changes without additional capacity. I have referred to these few facts to confirm that private enterprise is not only alive, but is kicking all right.

Private Enterprise would have shown perhaps a much better and a more impressive record of achievement, if it had not to work under a certain set of circumstances of which you are all so painfully aware for the last few years. I was on a Committee, which was asked by the Reserve Bank to consider the circumstances under which Private Enterprise was functioning and to explore ways and means of helping Private Enterprise particularly in the financial sphere. We had a very good opportunity of studying the situation in different parts of the country, and the unanimity of opinion which was represented to the Committee was that Government’s economic policy in the last few years had created an atmosphere of uncertainty in which naturally incentives are likely to be at a low ebb and that capital had been rendered very shy.

Even if you refer to the First Industrial Policy Statement of April 1948, the threat of nationalisation which was uttered in respect of basic industries has served as a serious disincentive to further industrial effort in the country. Nationalisation of Airlines dealt a very serious blow to confidence and, as a matter of fact, it has created an atmosphere of crisis of confidence which still continues. I am very surprised that the charge of lack of incentive or enterprise should be laid at the door of Private Enterprise when it is too well known that it was only through Private Enterprise that a first-class international air service was built up within a comparatively short period. Nationalisation of Airlines gave a rude shock to confidence amongst the investing public and since then we have found it increasingly difficult in attracting the average investor to subscribe to any fresh industrial enterprise.

Nationalisation of the Imperial Bank and recently Nationalisation of life Insurance have dealt further blows to Private Enterprise and have made capital more and more shy. I have been trying to look up the new Industrial issues during the last 8-9 months, and I have not come across, perhaps with the exception of one or two, any public issues for new industrial enterprise which has been supported by the investing public. The Industrial Policy statement of this year has certainly created further apprehensions not only in the minds of business men but of the investing public in general. The tragedy of the situation is this-that with a few exceptions, Indian business men and Indian public in general have not shown any due apprec6ation of the implications of this policy. Even a man like Sir John Strachey, who visited India some months ago, in his report has pointed out, although he is a man who has a definite Leftist bias, he was really surprised that when the Industrial Policy Statement was issued some Indian business men definitely welcomed it, while, most of them in general showed apathy or indifference about it.

I will now come to the second criticism, viz., that “Private Enterprise results in concentration of economic power”. In this connection, I have particularly to ask members of the Commerce Graduates’ Association to read an article which recently appeared in the Tata Quarterly of April-July which deals in detail with some structural aspects of industry in India. The article in a very objective manner examines the problem whether in view of the fact that particularly in the last few years when demand has been outstripping the supply position generally in the country there has not been a trend towards the establishment of a sort of monopoly by Indian Industrialists. If you study that article, you will agree with the writer of the article that applying any test, which is usually applied to the scrutiny of the establishment of a monopoly in any branch of economic activity, you will come to the conclusion that no such thing has happened in India.

The establishment of a monopoly for one thing suggests that those who are interested in the manufacture of particular products or commodities get together and manipulate the prices of these products or arrange production in such a manner that prices can be whipped up to the detriment of the community in general. An examination of the working of a number of leading industrial units in India, relating the price trends to the growing demand for the products, will lead to the objective conclusion that there is no basis of even an attempt to establish monopoly in #any of these industries in India. But when critics talk of concentration of economic power, they do not so much mean the establishment of monopoly, but what they really mean is that there are only a few industrial firms which are interested in a large number of industries, and, therefore, exercise control over them. In the first place, I need hardly point out that this betrays a lack of understanding of the basis of Joint Stock Enterprise. The basis of Joint Stock Enterprise is this: however big, influential and wealthy a firm may be, the magnitude of modern industrial operations is of such a character that no single firm can get together all the monetary resources to make any such enterprise possible. For instance, in one of our leading companies, the Tata Iron and Steel Company, there are about as many as 42,000 shareholders. It is true that the creditworthiness of some of the firms in India, their past record of achievement, enabled them to mobilise the savings of hundreds and thousands of small investors which alone make industrial enterprise in the modern sense possible.

Legislation was recently undertaken in the shape of amendment to the Indian Companies’ Act which goes far enough to break any such concentration if it exists in the country. But conceding for a moment, the concentration of economic power in the hands of a few people, it is forgotten that in an underdeveloped country like India you cannot expect hundreds and thousands of people who could be promoters of industries. If one studies the economic history of a country like Japan, for instance, or even of Germany, it is the pooling of resources and the working together of two or three big firms which made possible the industrial progress achieved in these countries.

There is one other important reason which might explain why industrial development in the last few years could not be quicker than what it has been. We who work in the private sector are believers in planned development. Planned development does assume some sort of regulation. But such regulation should not become restrictive as it has been in India. Take for instance, the Industries Development and Control Act and the licensing scheme which it has put up. Even if you think of starting an industry on your own, unless you satisfy certain norms which have been established by the Planning Commission, you are not likely to get permission to go into that industry. There are also certain administrative procedures and my Committee was particularly shown definite instances of administrative procedures where so much of red tape was involved that a number of industrial proposals which were put up in Madras and Bangalore had to be abandoned since the promoters got simply tired of travelling from Bangalore and Madras to New Delhi and back. It is not out of place to point out to the Government that in the interest of the industrial development of the country, some of these administrative procedures will have to be considerably simplified.

Another subject of topical interest is the publication of a letter addressed by Mr. Eugene Black, Chairman of the World Bank, to our Finance Minister, Mr. T. T. Krishnamachari. The genesis of the letter is this: a few months ago, the World Bank sent out a mission-the World Bank has the practice of sending out missions to different countries getting loans from the Bank to make periodical surveys of economic conditions in those countries. The mission, after surveying the situation and after having very intimate talks with Government officials, Planning Commission and Ministers, submitted their report to the World Bank. In that Report, within the short space of about 18 paragraphs, the mission has highlighted the main elements of our economic situation. In one paragraph the mission writes thus:

“The importance of private enterprise in the continuing economic development of the country is another factor which we would like to stress. We appreciate that the Second Five Bear Plan offers an opportunity for the ‘co-existence’ and simultaneous expansion of both the public and private sector and we have noted with gratification that the Prime Minister and other responsible Ministers have emphasised the need for Private Enterprise. Nevertheless, we believe that the importance of private business has not yet been sufficiently recognised and publicized. The record bears out the fact that private enterprise has performed creditably during the last five years with respect to both investment and production. In the organised sector of manufacturing and mining private business has contributed 90% of the increase in net output during this period. Owing to the capital-intensive nature of much of the contemplated public investment in Industry and mining during the Second Plan, Government plants and mines are expected to contribute only 29% of the anticipated increase in net output of mining and manufacturing as compared with a 54% share in the total planned investment. On the other hand, private business in this sec- tor is expected to account for 71% of the rise in net output. Considering the probability that the villages and small-scale industries may fall considerably short of the targets set for them by the Plan, the importance of the organised private sector becomes even more evident. It is, therefore, vital that the private sector be given adequate incentives and resources to enable it to make its requisite contribution.”

On the basis of this report, Mr. Eugene Black addressed a letter to our Finance Minister, Mr. T. T. Krishnamachari. In the course of that letter Mr. Black has said:

“In making my own comments, I should like first to emphasise once again my conviction that India’s interests lie in giving private enterprise, both Indian and foreign, every encouragement to make its maximum contribution to the development of economy, particularly in the industrial field. While I recognise that the Government itself must play an important role in India’s economic development, I have the distinct impression that potentialities of private enterprise are commonly under-estimated in India and that its operations are subjected to unnecessary restrictions there.”

This letter has created a little flutter in certain dovecots. I do not know on how many occasions we have been told by the highest in the country that distinguished foreigners who are visiting India have been terribly impressed with the progress that this country is making. This is perhaps the first occasion when a friendly critic has dealt with a few things in a very outspoken fashion. I can personally vouch for one thing-that Mr. Eugene Black is a real and sincere friend of India. I have reasons to tell you that he earnestly desires that India should develop economically at a rapid pace. But Mr. Eugene Black also is a man who by his extensive knowledge of conditions in different parts of the world is convinced that there are certain well-proved and well-tried methods of economic development which have resulted in substantial progress in many countries of the world and there is no reason that one could see of a hasty departure from these proved and well-tried methods. It is after a very close study of conditions in India as reported to him by the mission, and also because of the great personal interest he takes in watching the progress that India is making, that he has expressed views and tendered some advice which one could expect will be taken in the same spirit in which it was offered. I must say that the reply given by the Finance Minister is a very courteous, dignified and understanding reply. On the other hand, the criticism that we hear from other quarters appears to be rather unwarranted. It appears to be based again on the same thing to which Mr. Black refers–doctrinaire and ideological approach to the problems. There are certain people highly placed in this country who simply refuse to come down to earth and face problems in a realistic manner. I would like to pay my personal tribute to Mr. Black for the service he has rendered to India particularly at this critical juncture when we want a little more realism in the formulation and implementation of our economic policy. I am not referring to other parts of Mr. Black’s letter or to other suggestions which have been made by the World Bank Mission.

I am glad that the views held by some of us are being fully confirmed by the conclusions given by the World Bank Mission in its report in a matter like the Textile Policy. The textile problem is a very simple problem provided it is approached in a realistic way. Money worth crores is being pumped into circulation. How many people, who had no employment before, or who had no adequate employment, have started earning! In a poor and underdeveloped country like India, the two essential things to be provided are – food and clothing. The demand for food and cloth is on the increase and if our economy is to be sustained on a largely independent basis, it will be the first and primary responsibility of Government to see that demand does not outstrip supply. It is a very simple problem, and instead of tackling the problem in a realistic way, ideological and doctrinaire approach is brought to bear on the solution of the problem, with the result that there is nothing else but tinkering with the problem. Merely putting additional excise duties or advertising what are considered as fair prices will not result in producing additional cloth which is being needed every day by the country.

There is, however, one very interesting statement made by Mr. T. T. Krishnamachari in his reply to Mr. Black’s letter. Mr. Black refers to State Enterprises and Private Enterprises, and Mr. T. T. Krishnamachari of course thinks differently on the relative importance of the two sectors. He makes a bold statement that although the experience of State Enterprise has not been very long, at least in some cases State Enterprise has been found to be more efficient than Private Enterprise.

In the course of my activities in the Forum of Free Enterprise, I have had to answer questions in different places. In Calcutta I was pointedly asked whether I had any opinion to express on the working of State Enterprises. In any case, it would be fair to State Enterprise to say that the experience has been so short that it is premature to express any definite opinion. However, since Mr. T. T. Krishnamachari has found it fit to make up his mind that State Enterprise had been in some cases more efficient than Private Enterprise, I can only suggest to him that he should ask for some impartial assessment of the problem. We, in Private Enterprise, are very willing to learn. The more we learn and the more we improve; it is better for us and the country. Therefore, if Mr. T. T. Krishnamachari would call for an impartial assessment of the working of State Enterprise, Private Enterprise will have a lot to learn.

Finally, I will examine if Private Enterprise and Democracy are incompatible. Coming as it does from the highest in the land, it does need very close consideration and examination. I would, however, like to state that there are a number of thinking people in India who not only do not agree with the view but on the contrary honestly believe that if Free Enterprise is not allowed to continue in this country, subject of course to our accepting planned development of the country and the necessary regulations involved, and if Free Enterprise is going to be thwarted and restricted in its operations, it can only result in a serious diminution of the democratic way of life if not its ultimate destruction. I for one have been thinking for some time past and trying to understand if this statement could be correct-that Private Enterprise and Democracy are incompatible. Either I do not understand the content of democracy or I cannot understand the meaning of the statement “Private Enterprise and Democracy are incompatible.” As a matter of fact, we, particularly in the Forum of Free Enterprise, find our view confirmed by thousands of people in the country that Democracy, which is a blessing we enjoy and the Democratic way of life which has been assured to us in our constitution, is likely to suffer very severely if Free Enterprise is not allowed to be practised in this country.

Access the original document here.

First Published by the Forum of Free Enterprise in November 1956.

Other editions of the publication can be accessed at Indian Liberals, an open, multilingual digital archive committed to preserving liberal voices in the Indian public sphere.