An architect by training and the son of venerable Parsi entrepreneur Homi Mody, Piloo also had a long political career as a parliamentarian

“I am a CIA Agent,” read the placard on a politician in the premises of the Indian Parliament on one fine day in the 1970s. The pronouncement was a jibe at Indira Gandhi’s cynical approach towards her opponents. She would dub politicians the agents of US imperialism who sought to curtail her pro-people agenda. At the receiving end of her populist demagoguery were often the members of the Swatantra Party. And understandably so, because their eloquent advocacy of markets and liberalism had created consternation for the failed socialist government. The witty politician in the act was Piloo Mody. With a recourse to placard humour, he blunted the jingoistic politics of Indira Gandhi.

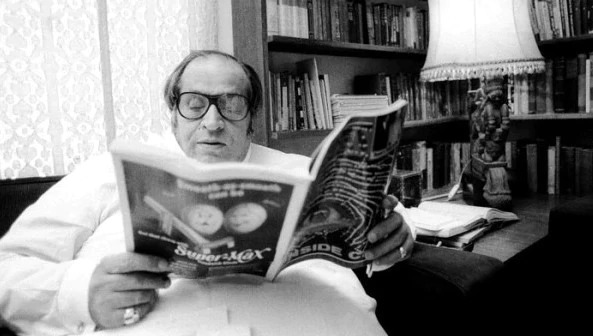

An architect by training and the son of venerable Parsi entrepreneur Homi Mody, Piloo also had a long political career as a parliamentarian. However, there is a clear lack of published material on his ideas and legacy. Much of the press coverage reveals his good sense of humour which added joy to the parliamentary sessions. He was also a vocal oppositional voice during Indira Gandhi’s rule. After the imposition of Emergency in 1975, he was one of the first politicians to be put behind bars under the provisions of the Maintenance of Internal Security Act. A close friend of Indira Gandhi though, Piloo Mody was offered conditional release which he rejected multiple times. Later in parliament, he vocally supported the bid to repeal the draconian act.

Author and parliamentarian Swapan Dasgupta recalls that Piloo Mody would visit the prestigious St Stephen’s College to address the student community. His witty take against the prevailing socialist narrative would draw a standing crowd. For such an unusual politician by Indian standards, it is rather tragic that Mody didn’t dabble much in writing. During the jail stint, he worked on the book titled Democracy Means Bread and Freedom. Called a liberal polemic by one reviewer, the book was his attempt to describe the meaning of democracy. Piloo Mody argued for a limited role of the state in the book to strengthen democracy. For him, decentralisation was the way for deepening of Indian democracy.

While he began his political career with Swatantra, the death of Rajaji and subsequent defeat of the party in 1971 led to an existential crisis. Minoo Masani put in his resignation papers accepting the responsibility for the defeat. In the last general meeting of the party in 1974, Piloo Mody decided to merge the party with Charan Singh’s Bhartiya Kranti Dal. The decision came under fire from the liberal intelligentsia for understandable reasons. However, as S V Raju admitted, the party was already in terminal decline. Raju traced the decline of Swatantra to Masani’s tenure as the president. He was a more efficient organiser-ideologue than the leader. The vacuum created at the organisational level and his lack of popular appeal probably caused damage to the party’s prospects in elections.

I would also argue that the lack of a strong cadre added to the decline as the star leaders either passed away or left the outfit. Swatantra was able to attract people based on leadership and agenda. It was unable to create a loyal vote base though because it lacked organisational setup. Mody later went on to join the Janata Party and served as a parliamentarian till death. In one of his last interviews, he described his plan to create a new political party. Nav Nirman was intended to be a political movement of honest and dedicated individuals who would take out hours from their schedule to serve the citizens at the booth level in a constituency. His utopian vision of decentralised political activism though didn’t come to fruition. The project was left midway due to his death.