Minoo Masani’s Bombay-based journal, Freedom First was an undeniable force for safeguarding people’s rights and liberty during the Emergency. The following essay encapsulates the role the journal played in enhancing ideas of liberalism in India.

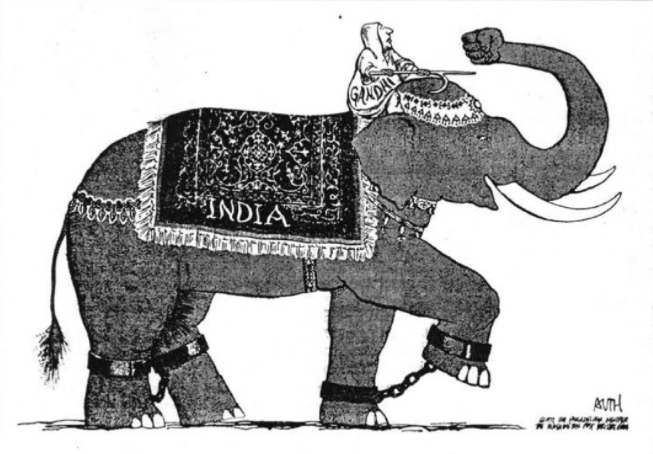

Not only did the promulgation of the Emergency saw the suspension of electoral democracy but also the curtailment of press freedom. The state of affairs was best summarized by Lal Krishna Advani’s remark that . While major media houses succumbed to the authoritarian pressure, Minoo Masani’s liberal journal Freedom First stood as a notable exception in its resistance to the Emergency. To be sure, Masani’s magazine was not the only media platform to resist the censor diktats. But Freedom First undoubtedly played a remarkable role in advancing civil liberties, more so given its small clout and reach.

Masani’s Freedom First was in the proverbial eye of the storm when it comes to press censorship. In the second half of 1975, after the promulgation of Emergency in June, Freedom First ceased publication. The Bombay-based journal’s incorrigible democratic editor Minoo Masani had enough with the diktats of the censor. Instead of putting up with the order to prohibit eleven items from publication, he rather decided to stop publishing the magazine and also filed a case in the Bombay High Court. Fought by Soli Sorabjee on Masani’s behalf, first the judge R P Bhatt’s and later the division bench of D P Madon and M H Kania’s verdict saw the censorship order being quashed. With this victory, Freedom First resumed its publication in January 1976. In the coming months, the pages of Freedom First would see Masani’s constant railing against the Indian democracy’s authoritarian turn under Indira Gandhi.

Saving the Constitution

In response to a slew of constitutional changes brought to bolster the Emergency, Masani often cited his laurels as a founding member of the Constituent assembly to bolster his case. He also rhetorically pointed out that Indira Gandhi and her sycophants’ bid to overturn constitutional provisions was a turn away from the vision of Jawaharlal Nehru, Bhimrao Ambedkar, and Sardar Patel. Masani was, in particular, worried about the discarding of federalism due to the increased executive centralization during the Emergency. After the removal of state governments in Tamil Nadu and Gujarat, Masani lamented about the effective demise of federalism in India: ‘Now there is no State government left of a different political colour from that at the Centre. India has for the time being become a unitary state.’ For Masani, the danger of centralizing overreach lay in paving way for fissiparous tendencies. The argument went that a country as diverse as India ‘needs a federal structure’ and the lack of reasonable autonomy for states would have led to a separatist tendency.

In light of the Swaran Singh Committee recommendations, Masani again defended the constitution as promulgated by India’s founding fathers. He argued that the proposed fundamental duties should be voluntary in nature, not to be enforced by the sovereign in law. Gandhi’s warning of the state as the greatest threat to human liberty was also invoked repeatedly in Masani’s writings. To him, the three essential elements of the constitution which constituted basic structure included fundamental rights, federalism and state rights, and the right of presidents and governors to dissolve the legislatures and cabinets. The 42nd amendment bill, he argued in Bangalore, had watered down the basic doctrine of the constitution in favor of a move towards ‘a centralised and unitary government’. On the importance of fundamental rights to human freedom, he wrote: ‘There are certain rights that the citizen possesses that cannot be subjected to the whims and fancies of the majority of the day and these are rights that we listed and described as Fundamental Rights.’

Advancing Liberalism

Masani clearly saw the Emergency’s threat to liberal democracy and opposed different manifestations of the threat. For him, the invocation of Emergency amidst the prevailing situation was unconvincing as there ‘was no clear and present danger to the security of the State.’ The so-called positive steps undertaken by the Emergency regime might as well have been achieved without the severe cost. For all the gross violations of human rights and suspension of fundamental rights, Masani was careful enough to see the Emergency as a limited form of authoritarianism, not a turn towards fascism or a communist dictatorship. In his analysis of the Emergency in Encounter magazine (republished later in Freedom First), Masani couldn’t avoid the temptation of playing a prophet whose pontifications came true. The Emergency proved correct his warnings in the 1960s about the incompatibility of the democratic process with a highly controlled planned economy and public sector monopolies, wrote Masani.

One of the justifications provided to legitimize the suspension of political rights during the Emergency included the promise of prosperity under a centralized, authoritarian regime. However, the democrat in Masani took the opportunity to highlight the link between democracy and economic development. He pointed out that countries with a functioning democratic system were also more successful at providing economic betterment to their citizens. On the famous Bread versus Freedom choice offered by the apologists of totalitarian regimes, Masani made his choice clear: ‘There is no clash between bread and freedom or between elections and economic prosperity. On the contrary, by and large, they go together.’ Years later, S V Raju’s editorial on the Tiananmen Square massacre in Freedom First would deploy a similar argument against the CCP regime.

Supporting Resistance

Freedom First not only did feature Masani’s musings on the prevailing situation but also gave coverage to the acts of resistance against the Indira regime. Interestingly though, when the Emergency was in operation, the magazine did not discuss the clandestine resistance movement and neither did it cover RSS’ role in the anti-Indira coalition. This omission can perhaps be accounted for by the liberal tenor of the editor who believed in rule of law, free speech, and public debates. Be that as it may, Masani published in the April 1976 issue the Maharashtra Bar Council’s July 1975 resolution. The resolution appealed to the President to revoke the proclamation that made the Emergency possible. The delay in the publication of the resolution can be explained by the censorship order which was later struck down by the Bombay High Court.

Apart from the Bar Council resolution, the magazine also covered the draft statement on the formation of a new party that would culminate in the Janata experiment. While S V Raju was sympathetic to the initiative, his editorial took objection to ‘egalitarian’ and ‘socialist’ pieties which found a mention in the draft. Apparently, Raju’s liberal sensibility made it difficult for him to accept the new party advancing the same old socialist talking points as their opponent Mrs. Gandhi. Later, Minoo Masani would express satisfaction at the improved manifesto of the Janata Party as it dropped ‘objectionable references to an “equalitarian society” and “total planning”.’

Further, the March 1977 issue featured a sharp commentary on the suppression of Justice H R Khanna for the position of Chief Justice of India despite him fulfilling the seniority criteria. The explanation was not difficult to find: ‘Mr. Justice Khanna had distinguished himself by passing down a minority judgment asserting the right of the citizen to the writ of habeas corpus even during the Emergency. The New York Times had remarked that the time would come when a statue of his would be erected in every city of India.’ The same issue also covered the statement from Freedom House in honor of C R Irani who received the prestigious Freedom House Award. Irani was the managing director of The Stateman and had fought a courageous battle for press freedom during the Emergency.

Conclusion

The Cold warrior in Masani occasionally interpreted the events of Emergency from an anti-USSR prism. Two such instances could be found in the pages of Freedom First published during the Emergency. In the May 1976 issue, the punctilious Masani took a shot at Law minister H R Khanna for advocating watering down of Article 226 of the Constitution which empowers High Courts to admit writ petition. Masani argued that Gokhale’s coincidental meeting with the leader of a Soviet Law delegation might have something to do with the proposed measure: ‘His Soviet mentors will have no doubt nudged the Law Minister’s elbow in case this was needed.’ Second, the August 1976 issue saw a TASS report juxtaposed with The Times one on India’s authoritarian turn. The TASS commentator took umbrage with the western critique of ‘cardinal socio-economic transformations’ of the Indira government under the Emergency. The Times report, on the other hand, captured the British discontent and disappointment with India’s recent authoritarian turn. The underlying implication for Masani was clear: Indian democrats should not be in two minds about their friends abroad. The communists in USSR certainly weren’t the ones.

It was in 1977 that Indira Gandhi finally decided to lift the Emergency and conduct elections again. In the wake of Janata’s electoral success in the 1977 general election, a jubilant Masani described it as not so much a victory for the Janata Party but a rejection of the dictatorship. As a cautious democrat in vigil, he took the opportunity to suggest remedies for democratic backsliding. The recommendations included the adoption of proportional representation system, independence of the judiciary from the purview of parliamentary majority, maintenance and strengthening of federalism, and limited government. Finally, Masani’s abiding belief in the redeeming feature of common folks of India led him to argue for cultivating citizenship and a voluntary sense of service. His idea of grassroot democracy comprised of voluntary institutions like consumer associations, environment protection groups, and the Bombay Civic Trust.