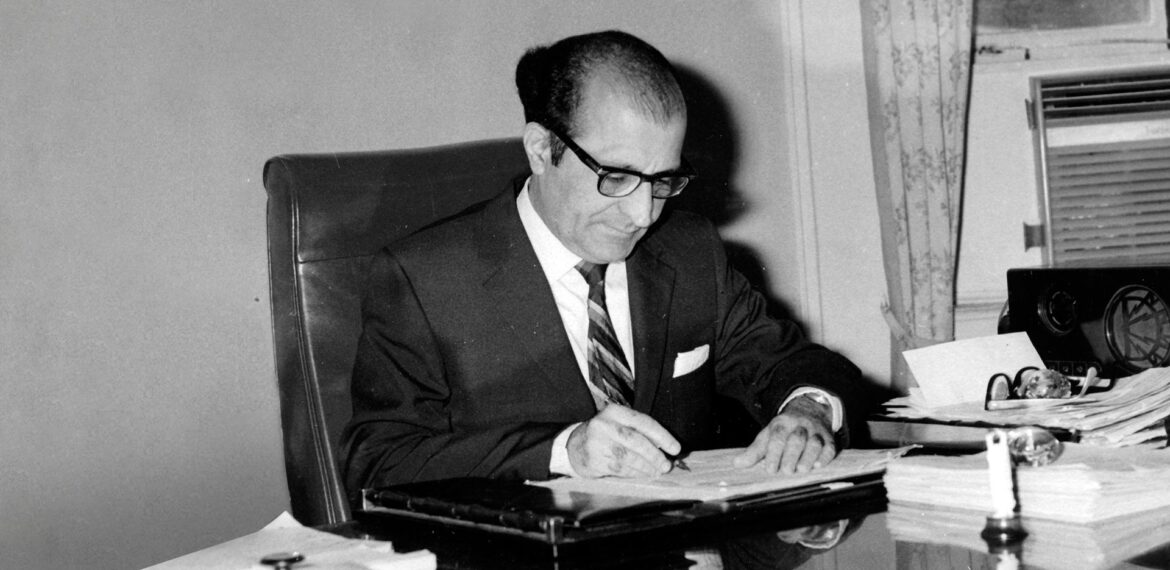

In 1957, the courtrooms in India witnessed a high-stakes legal battle. It was fought in two innings, first in the Bombay High Court and later in the Supreme Court of India. The Supreme Court’s verdict in R. M. D. Chamarbaugwalla vs. Union of India outlined core principles to determine if any economic activity constituted gambling. Even after 69 long years, the doctrines applied to interpret the Constitution inform our understanding on matters pertaining to gambling and betting. In the light of the recent ban on online real money games by the Union Government, this oft-forgotten legal dispute demands a fresh glance from anyone interested in public policy. One of the brightest advocates in independent India represented the parties involved in this legal conflict. Nani Palkhivala represented R. M. D. Chamarbaugwalla, the founder and Managing Director of R. M. D. C. (Mysore) Limited against the State of Bombay and later against the Union of India.

The Witch-hunt

The state legislature of Bombay regulated gambling and betting through the Bombay Lotteries and Prize Competitions Control and Tax Act, 1948. This law made licences mandatory for legal recognition. It further imposed taxes on the amounts received by promoters of licenced competitions. Renewal of licences was subject to administration’s discretion. To avoid taxes, stricter controls, and uncertainty, Chamarbaugwalla shifted his operations to the neighbouring State of Mysore. Anyone who understands the distinction between tax avoidance and tax evasion would appreciate this as a rational and economic choice.[1] Chamarbaugwalla ran a crossword prize competition in his weekly newspaper ‘Sporting Star’ printed and published from Bangalore in the erstwhile State of Mysore. He operated from this alternative location and continued to conduct the crossword competition in the State of Bombay until the state law was amended to his disadvantage.

The Bombay Lotteries and Prize Competitions Control and Tax (Amendment) Act, 1952 deleted the clause that excluded prize competitions from newspapers ‘printed and published outside the province of Bombay’.[2] It extended the law’s reach to include operations of R.M. D.C. (Mysore) Limited. Moreover, it inserted Section 12(A) introducing a new tax for such competitions. Chamarbaugwalla was already paying substantial tax to the State of Mysore on his gross receipts from the crosswords. The amended rules increased compliance and operational costs and substantially eroded the profits of Chamarbaugwalla. Therefore, he challenged the Act and the amended rules.

Palkhivala Stunned the Government

The first round of legal action was played out in the Bombay High Court. The main contentions of Nani Palkhivala against the validity of law are summarized below.

- The amendments introduced in 1952 were extra-territorial or outside the jurisdiction of the State of Bombay.

- The prize competitions under scrutiny were valid commercial or trade activities. Therefore, the disputed Act fell within the scope of entries 26 and 60 of the State List in the Seventh Schedule of the Indian Constitution.[3] This meant that these enterprises enjoyed the constitutional protection of Article 19(1)(g) and Article 301 against unreasonable restrictions.[4]

- The impugned act was meant for gambling, whereas the crossword prize competition was hardly a lottery or chance-based competition. Instead, it required exercise of skill and considerable knowledge. The Indian Constitution had protected the games that involve skill under the right to trade. Games of chance would not have enjoyed the same protection.

The single judge bench of the Honourable High Court delivered a verdict in favour of Palkhivala. It ordered the State of Bombay to refrain from implementing the impugned Act and allowed the petitioners to carry on the business as usual. The State of Bombay appealed in the High Court. The Court of Appeal upheld the ruling of the trial court while differing in some respects.[5] It held that the State of Bombay was competent in enacting the Act under dispute. The Court held that prize competitions were valid businesses and they did not constitute gambling. Therefore, Article 301 was applicable to prize competitions. Moreover, the tax imposed on prize competitions under Section 12(A) was to be seen as a tax on trade or profession under Entry 60 of List II. Lastly, it argued that the prize competitions including lottery-based ones, were not against public interest.

Supreme Court : The Final Frontier

After struggling to get judicial clearance, state legislatures chose a different path. Using provisions under Article 252(1), several Indian states passed resolutions authorizing the Union Government to enact legislation on prize competitions. It was unusual because ‘gambling and betting’ which is a subset of prize competitions, is a subject enumerated in the State List. Regardless, the Union Government immediately passed the Prize Competition Act, 1955.

The law limited the total prize value to Rs.1000/- per month and the number of entries to Rs. 2000/-. It introduced licences for all prize competitions falling under the prescribed limits. It mandated strict maintenance of accounts and laid down penalties. The licences could be suspended or cancelled.[6] This law effectively crippled the operations of Chamarbaugwalla and others. This led to Chamarbaugwalla and several aggrieved others to challenge the Prize Competition Act, 1955.

Palkhivala firmly argued that the law was unconstitutional in its entirety. He based his argument on three major pillars.

- The definition of prize competitions under the law was too broad. It was so unqualified that along with gambling its scope included competitions that required a substantial degree of skill.

- For skill-based competitions any legal provision limiting the prize value and restricting the number of entries was not reasonable regulation, but in effect prohibition.

- The law constituted a single, indivisible enactment. Since it misassessed skill-based competitions, the entire law must be struck down even if it legitimately restricted some chance-based competitions.

The Union Government contended that gambling activities were not trade or commerce. Therefore, the law was intended to regulate competitions with characteristics of gambling. It further conceded that the law was indeed broad. It argued that the provisions of the law were void for skill-based games. The government argued that the valid parts applicable for gambling could be separated from invalid parts related to skill-based competitions. The government was suggesting that the law automatically would not be applicable to skill-based competitions.

In its verdict, the Supreme Court declared gambling res extra commercium.[7] This meant gambling would not be considered commerce. Since gambling would not be a lawful trading activity it would not enjoy the protection of Article 19(1)(g). Contrary to Palkhivala’s plea, the Supreme Court rejected a purely textual reading of the law. While recognizing that the law was partly void, the Supreme Court embraced the doctrine of severability. The Supreme Court upheld a law which was partly valid and partly invalid, echoing the argument made by the legal representatives of the Union Government. Earlier, the doctrine of severability had only been applicable in cases where the government exceeded its subject matter competence. It had not been applied when the government violated fundamental rights. The Supreme Court opined that the principle of severability was applicable even when the partial invalidity of the Act arose from its contravention of constitutional limits in the form of fundamental rights.

Summing Up

Independent India’s legal journey has come full circle with the promulgation of the Promotion and Regulation of Online Gaming Act (2025). This law seeks to address the social and economic risks associated with the digital gaming industry. The law is admittedly rooted in the proverbial ‘good intentions’—specifically protecting vulnerable youth from predatory designs, addictive algorithms and subsequent financial ruin. This legislation marks a legal milestone in conceptualising safeguards for Indian citizens from what it considers an exacerbating public health problem. It mentions a wide range of problems such as social, economic, and national security threats. However, the law bans Online Money Games in their entirety. The current broad-brush approach is reminiscent of the Indian State’s position in 1957. It blurs the legal distinction between online money games of skill and money games of chance—a distinction upheld by the Supreme Court since 1957.

The doctrine of severability applied by the Supreme Court in Chamarbaugwalla vs Union of India sets a somewhat frightening precedent. By severing bad parts of a law, rather than striking the whole thing down, the Court essentially saves poorly drafted legislation. It allows the government to be overly broad in its lawmaking. Let us imagine its implications for the online gaming industry. The degree of skill involved in a particular online game will ultimately be decided in a court of law. This will not only continue to burden the judiciary with scrutinising vague laws, but also allow the Union Government to keep introducing similarly broad laws. Persons and companies adversely affected by the law will be compelled to approach the court. The legal battles that would ensue will take several years for resolution or settlement. It would increase the costs for the companies developing online money games. This does not paint an encouraging picture for enterprises in India. This can create a ‘litigate-to-operate’ environment or an endless, exhausting hurdles-race that treats every entrepreneur as a gambler until proven otherwise in court.

This is saddening given the abundant potential the industry holds in terms of growth and employment. In 2024, the online gaming industry was a $3.7 billion ecosystem. It was projected to reach $9.1 billion by 2029.[8] The recent blanket ban has not just halted growth, it has caused flight of investments, and has triggered economic contraction in the sector.

Perhaps, Nani Palkhivala foresaw the possibility of such an unintended outcome. Therefore, he staunchly argued for treating exceedingly broad laws as single, indivisible enactments before striking them down fairly and squarely.