Produced below is an excerpt from an article by A. Ranganathan called “Tagore’s Humanistic Approach to Indian Nationalism,” where the author explores Rabindranath Tagore’s unique perspective on Indian nationalism. The article delves into how Tagore distinguished Indian nationalism from European forms, emphasized the importance of cultural exchange with the West, and believed that true freedom extended beyond political independence into the realm of the mind and spirit.

In order to appreciate the significance of Tagore’s most precious gifts to our country, it is necessary to view the backdrop of the ‘Indian Renaissance’ in its historic setting. The transition from medieval to modern India, which resulted in that great cultural awakening known as the ‘Indian Renaissance’, was effected by Raja Ram Mohan Roy. Indeed, the day of Raja Ram Mohan Roy’s birth was also the birthday of modern India. A new spirit was abroad, a new buoyancy of life symbolizing the streaks of a rosy dawn after the long medieval night which had enveloped India for centuries.

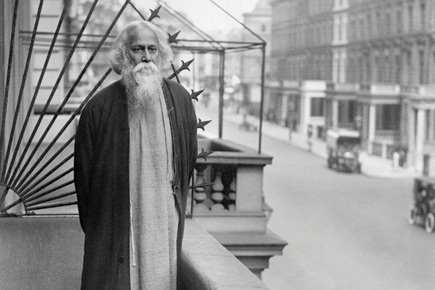

The various forces which have contributed to the shaping of modern India originated in the mind of Raja Ram Mohan Roy. And Tagore not only constituted a historic link in the long chain of India’s cultural evolution, but was also the prophet of the Indian Renaissance heralded by Raja Ram Mohan Roy.

Tagore had drawn the vital distinction between the Western Nation and the spirit of the West in his celebrated lectures on “Nationalism”: “This reign of law in our present government in India (the British Government) has established order in this vast land inhabited by peoples different in their races and customs. It has made it possible for these peoples to come into closer touch with one another and cultivate a common aspiration.”

Indian nationalism was an aspect of the ‘Indian Renaissance’ movement. It is well to remember, however, that the nature of Indian nationalism, although influenced by European nationalism, is entirely different from European nationalism. Indian nationalism succeeded in welding the political unity of India, whereas European nationalism split up Europe into several nations based on ethnic considerations.

If Swami Vivekananda could be regarded as the prophet of Indian nationalism in its philosophical (Vedantic) context, Dr. Ananda Coomaraswamy, who had spent much of his career at the Boston Museum, can be looked upon as the most articulate exponent of the aesthetic philosophy of Indian nationalism. And Tagore’s approach to Indian nationalism differed from that of his distinguished contemporaries, who had merely Indianized the concept of Mazzinian nationalism. Tagore’s greatness lies in the fact that he infused the spirit of poetry into the Indian national movement. In the final analysis, Tagore had universalized the concept of freedom.

‘Swaraj’, as Tagore interpreted it, was not a mere political actuality. It was a process which extended the frontiers of the mind. He was certainly opposed to the continuance of British rule in India. However, even in the heat of political controversies, he never lost his sense of perspective. In fact, he had relinquished his knighthood in the wake of the Amritsar tragedy of 1919. And our National Anthem was one of his greatest contributions to Indian nationalism.

Like Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Tagore knew the value of English and could foresee its impact on Indian cultural life. Tagore, who was profoundly influenced by Keats and Shelley, had felt that the impact of the English language on the mind of the Indian nation did not generate a process of cultural enslavement, but was the harbinger of a new era of creative consciousness. Western literary forms like the essay and the novel which became assimilated into the mainstream of our languages, and the brilliant contributions to modern science by some of our scientists, are some of the outstanding features of the ‘Indian Renaissance’.

Indeed, Tagore commented: “Gandhi Mahatma is making various efforts to make Hindi the language for the entire country. These efforts, however thriving today, may one day as well peter out.” And Tagore had hoped in his “Talks in China” that “the awakening of the East” would “impel us consciously to discover the essential and universal meaning of our own civilization.”

Viewed in the perspective of cultural history, the British impact on India resulted in a phenomenon similar to the effect of the Westernizing policy of Peter the Great. And today, there is undoubtedly a need for a rethinking of the philosophy of nationalism in its proper perspective. It is remarkable that Tagore had pioneered a new approach to nationalism in tune with the Time-Spirit. As the eminent historian of Nationalism, Prof. Hans Kohn wrote in his “A New Look at Nationalism”: “None has spoken more strongly against the cult of one’s own nation or nationalism than Vladimir Solovyov in Russia or Rabindranath Tagore in India, both men deeply rooted in the spiritual tradition of their community and yet wide open to the critical insight of the West.”

As pointed out by Prof. Hans Kohn, the possibility of a deeper cultural intercourse between India and the liberal West can arise only if we no longer allow our thinking to be channeled into widely accepted stereotypes about nationalism and its relation to liberty. “The time has arrived,” wrote C. E. Trevelyan in his “The Education of the People of India”, “when the ancient debt of civilization which Europe owes to Asia is about to be repaid; and the sciences cradled in the East and brought into maturity in the West may now by a few efforts overspread the world.” And this dispensation, which followed in the wake of Raja Ram Mohan Roy’s letter to Lord Amherst, was not regarded by Tagore as an invasion of Western ideas, but as a step towards the intellectual dialogue of cultures and civilizations.

Read the complete text and other articles from this issue of the Indian Libertarian here.