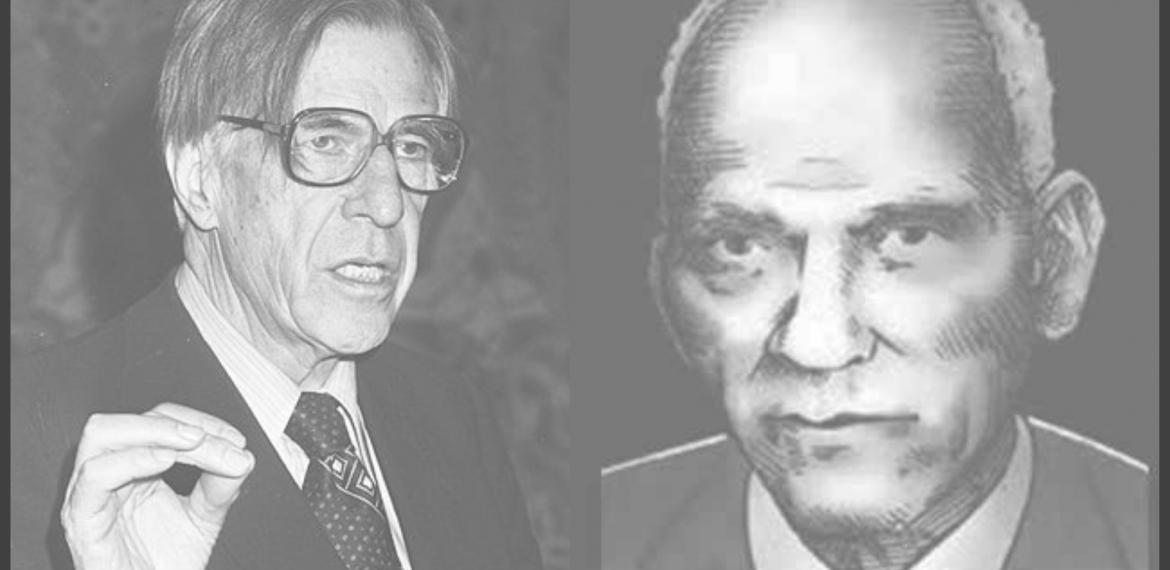

The following text is a reproduction of an article specially written for syndication by Indian News & Feature Alliance (INFA). Reproduced by Forum of Free Enterprise, in the article, Prof B.R. Shenoy counters Prof J.K. Galbraith’s (Canadian-American economist) claim that planning is crucial to economic development. He argues that consumer sovereignty and planning for the free market would lead India to economic development.

Professor J. K. Galbraith has made planning a theme of his weighty pronouncements more than once during his tours round India. At a Press conference in Ahmedabad, commenting on the fears expressed “‘in some quarters in India” that the present tempo of our planning might lead to an authoritarian regime, he observed that “lack of planning” in underdeveloped economies “carried a greater risk of leading to authoritarian regimes than proper planning”.

He utterly ridiculed these fears, saying that “whenever somebody wants to denounce something, he says it is likely to lead to authoritarianism.” In addition to planning, he continued, public ownership, agricultural price support, trade unions and large corporations had been accused, by different sections of the people, at different times, as precursors of authoritarianism. But their cry of “wolf” had proved false alarms. It was safe enough guarantee against this calamity, if the “spirit of democracy is deeply implanted in the mind of peoples and in their institutions”.

The logical basis of Prof. Galbraith’s conviction, which is widely shared in India, is simple. A country facing the problem of lifting itself from poverty and of providing a better life for its people would be condemned to frustration “‘without planning”; from the “discontent” born of the tyranny of unrelieved poverty, they might fall an easy prey to the promises of Communism. This danger can be averted by a “proper planning of its resources”.

It will at once be agreed that the greatest single problem before underdeveloped countries is their abject poverty. Everything hangs on its eradication. Failure to tackle it effectively might engender social and political instability, though the fear in this regard is often unduly overdrawn. The question is whether this central objective – the eradication of poverty – may be best and most speedily achieved through planning, as we have seen it in action during the past decade; and as Prof. Galbraith, a devotee of Indian planning, seems to understand the term. The answer centres round the problem of maximismg output from our meagre resources, as output provides the wherewithal for liquidating poverty. The faster the growth of output the sooner is poverty liquidated.

Any programme for maximising output cannot Ignore the prevailing extremely complex, pattern of pr~ duct10n of the Indian economy. Fully 50 per cent of the national product is from agriculture and about 70 per cent of the population lives on it. Agricultural production is in the hands of 67 million independent farmers scattered round the country, the average holding per family being 5.5 acres. Cotton textiles comprise about 36 per cent of industrial production. Textile output ensues from 478 mills, 80,000 to 90,000 powerlooms and 2 million handlooms. The remaining sectors, too, comprise tens of millions of independent production units. Save and except under the Communist steam-roller, this production set-up cannot change overnight, so to speak.

Two policy compulsions emerge from this set-up, if we must accelerate output. First, agriculture, textiles and the basic consumer goods Industries, which constitute the bulk of productive activity, must receive first claim on productive resources. Secondly, centralised planning – in the sense of state control over the allocation of resources – is not practical, though simpleton administrators might think otherwise. Centralised planning can only produce chaos and retard the hand of progress, when the planners have to deal with tens of millions of production units scattered round a sub-continent.

We have violated both policy compulsions in the name of planning. The Public Sector will appropriate in the Third Plan, 65 per cent of investment resources. The percentage was 57 in the Second Plan. These resources will go into heavy industries mammoth river valley projects and costly social overheads. Large parts of the remaining resources would also be forced into heavy industries and industries producing intermediate and other non-consumer goods, through exercise of the control over capital issues, import licensing, permits for raw materials, concessions and quotas.

This leaves little of the productive resources for use in agriculture and for producing cloth and the other consumer needs of the masses. Resources drawn into heavy industries would add to the national product, but an order of 14 per cent of their value; they would add an order of 36 per cent if employed in consumer goods industries and 65 per cent if employed in agriculture. The outcome of our developing heavy industries at the expense of consumer goods industries, and of developing both at the expense of agriculture, has been two-fold: Indian national income has risen during the past decade at an annual rate of about 3.5 per cent; and the consumption of food and cloth by the masses has declined,

or is semi-stagnant.

In the absence of planning-forced diversion of the largest bulk of Plan finance into wasteful projects-productive resources would flow into channels where they yield the highest output, through the usual market mechanism. Two results would ensue from this, simultaneously: first, national income might increase at an annual rate of 8 to 10 per cent; secondly, output of the basic consumer needs of the masses-principally, food and cloth-would go up simultaneously with the national product, as investments in these directions yield the highest returns and as economic activity would now be controlled and directed by the consumer, not by the Planning Commission.

This is not to say that, under the free-market system and the sovereignty of the consumer, there is no room for any planning. Orderly progress is inconceivable without planning. In the private sector, then, planning will be done by the millions of individual production units; in the Public Sector, by the state. The Public Sector will be confined to activities which cannot be effectively undertaken by private enterprise, e.g., the provision of an honest rupee, the rule of law, basic transport and communications standardisation of weights and measures, education and public health. In particular, the state should not stray into trade and industry, or interfere with the distribution of productive resources. To do so would be to upset the planning of millions of production units, to the detriment of the national product and social justice, causing untold human suffering in the Indian context of extreme poverty.

Thus, the “discontent” and possible explosion, which must ensue from the pursuit of the prevailing economic and social policies, carries the very “risks of authoritarianism”, which Prof. Galbraith thinks we would avert through the so-called “proper planning of our resources”. These risks cannot be averted with greater certainty than through planning for the free market under the banner of consumer sovereignty.

Planning for the free market has yielded blinding economic and social dividends wherever it has been given a chance. In the post-war world, it produced the first miracle in West Germany. It then spread, with as good or better results, to the other E.E.C. countries, Israel, Japan, Hong Kong, Spain and, latterly, the Philippines. The eagerness of U.K. to join the E.E.C., even risking severance from its political kith and kin, is evidence of the vitality of the new movement.

News of this powerful reaction away from statism has not reached New Delhi yet; nor the Indian universities generally, where economists still fondly cherish outmoded dirigiste doctrines, fancying them to be tenets of the nuclear era. The Galbraiths, Millikans, Rostows and Wards, not to mention the pronounced left-wingers like the Baloghs, Bettleheims, Langes and Robinsons – all sincere friends of India and hot favourites of our Government – through their expositions, probably stand in the way of our properly appreciating the tremendous potentialities of planning for the free market under the aegis of consumer sovereignty. The illicit beneficiaries of planning, now the power behind the throne, who, too, are champions of mass prosperity, are another great hurdle to be overcome. But neither economic nor social salvation is possible except through policies of economic and social freedom.

The task before the policy reformer is indeed overwhelming. The situation provokes the prayer; ”’Good Lord, protect me from my friends; against mine enemies I can defend myself.”

Previous musing: RAJA RAM MOHAN ROY ON PRESS FREEDOM