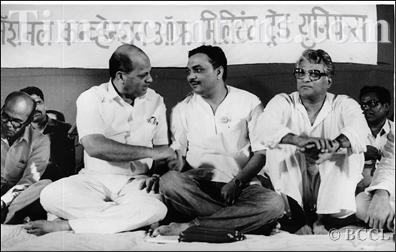

Sharad Joshi addressed his criticism against the government as well as the then labour movements in the country. According to him, trade unionism in India had taken a path far different from their predecessors in Europe. (Image Credit : The Times of India)

There’s no better or succinct way to introduce Sharad Joshi than by narrating an interesting anecdote that he shared in his book Khulya Vyavasthekade Khulya Manane. It gives a glimpse of his politics and personality. In 1996, the government employees of the Department of Post went on one of their routine strikes and this irked Sharad Joshi so much that he made an interesting offer to the government. He proposed that the government should let him run the department of Post. He challenged that he would not only employ just half of the existing number of workers but he would also give them only half of the current remuneration and still ensure the required level of efficiency to distribute all postcards from any major city in India to another within 24 hours. His challenge to the government may seem a bit foolhardy today. But the fact remains that at that time it took almost five days for a postal delivery to take place from one major city to another. We can not even fathom the unending delays for a letter or parcel to reach the remotest corners of the country.

Sharad Joshi addressed his criticism against the government as well as the then labour movements in the country. According to him, trade unionism in India had taken a path far different from their predecessors in Europe. The trade unions in nineteenth-century Europe emerged as a response to the nascent industrialization. The workers used strikes as a potent weapon to organize themselves and have their collective voice heard. These ‘have nots’ had no other option but to use such techniques. One must not forget that unlike today the working class of that time had very little role to play in political decision making. The franchise was limited and it often excluded the poor and the illiterate. The instrument of the strike was not easy to use. The workers would lose their daily wages and it would render them vulnerable to joblessness and dire hunger. The state would look at their strikes as a law-and-order problem and the police crackdowns used to be unbearable. Even if the state spared their lives, there was no guarantee that the goons hired by the owner of the workplace would be equally generous. The workers of the nineteenth century shed their blood and even made the ultimate sacrifice for basic economic rights.

Sharad Joshi acknowledged the higher ideals and causes for which these early unions fought. Having acknowledged those, he argued that much of these above-mentioned excesses were a characteristic of an early capitalism which hadn’t developed enough. Sharad Joshi ascertains that much of these evils were a function of an economy that was devoid of properly developed markets. However, when the doctrine of Socialism took roots in Europe, a simplistic and permanent dichotomy of ‘monstrous haves’ and ‘oppressed have nots’ was established. Many legislations alleviated the working class from earlier miseries. The workers got several concessions in terms of their salary, bonus, allowances and the security of a job. This overhaul occurred first in the private sector and then in the public sector.

Talking about the socialistic practices in India, Sharad Joshi argued that Socialism protected the rich industrialists from an international competition that never brought the best out of Indian producers. According to Joshi, socialism could never sustain without the licensing regime. It was a license – given to the industrialists to plunder the Indian consumers. While the Indian consumer used the substandard goods, the profits of these industrialists soared. The exponential growth in profits was not hidden from the union leaders. The smartest of leaders knew the extent of profit earned by the company owners. They also knew that many of these capitalists were not sharing the details of real profits with the workers and in turn threw peanuts at the workers.

The union leaders exploited such opportunities to advance their unrealistic demands for wage hikes. The owners of industries would have only two options; first, to raise the salary twofold or threefold and second to let the workers stop working and go on strike. If workers stopped working even for a day or two the owners would lose a humongous amount of money. Therefore, the reluctant capitalists would reconcile with the workers and make as many concessions as quickly as possible. This got converted into a trend where the union leaders started competing with each other. Blackmailing the capitalist became the quickest way to establish influence on the workers and prove their credibility as leaders.

If the economic reforms exposed the Indian capitalists to outside competition, they also reduced the vulnerability of the capitalist vis-à-vis the union leaders. After seeing the approaching liberalization of the economy, the industrialists turned more or less immune to the blackmailing of these trade unions. Therefore, upon hearing the news of the textile workers in Mumbai going on strike under the leadership of Dr. Datta Samant, far from being under pressure, the textile mill owners and their managers were ecstatic and thus unwavering!

Joshi argued that by the 1980s the tide had turned against the workers and in favour of the industrialists. Now the blackmailed capitalists of yesteryears weren’t entirely vulnerable as they had multiple options at their disposal to maneuver against the calls for a strike. They could take strict measures in the face of reduced productivity. These measures come in different forms – right from reducing the number of workers by firing inefficient and underperforming workers to hiring workers on a contractual basis. They could also terminate all operations if the business showed no promise or if it ran into the irreparable loss. As stringent as these measures may seem they were necessary, after all the industrialists didn’t have the option of printing more money to fulfil the whims and fancies of the workers on strike.

Unfortunately, these changes remained limited to the private sector. The government servants remained no less protected than the indigenous capitalists during the days of import substitution and socialism. The government jobs became prestigious due to the unreasonable amount of protection that the government granted to its workers. The government jobs became so lucrative that even doctors and engineers who could practice privately started contemplating and considering government positions. The protection provided to the government jobs created a political economy where the caste groups started demanding reserved positions in the recruitment to be able to enjoy the spoils of the spoils system called the government bureaucracy. Thus, the political demands of castes for quotas in government jobs can be traced back to the guarantee of security and economic benefits attached to these jobs.

Sharad Joshi draws our attention to another important fact related to the wages of Indian workers. He argued that the wages of Indian workers or servants are modest as compared to the workers and servants having similar responsibilities or performing the same tasks abroad. But if we compared the two based on their productivity and efficiency, the pay scales offered to Indian counterparts were higher than what they deserved.

This invited the economic crisis, and the government became bankrupt. The economic compulsions propelled the government to lay off the workers and adopt austerity measures. There was a growing realization that consumers deserved commodities and services of good quality and that license raj was becoming a hurdle. The License-permit regime was removed but the Indian economy was faced with new problems. There was an absolute dearth of good infrastructure. India didn’t have a steady supply of electricity and water; the roads were in a bad shape and the railways were inadequate. If India had to build a robust infrastructure it required capital and technology. Therefore, India was desperately looking for foreign investment. But the basic services like the postal service, telecom services, insurance and the banking sector were so obsolete that foreign investors would think a thousand times before considering India as a potential destination to invest their capital.

Joshi unequivocally asserted that when the nation was embroiled in economic distress these workers and government servants were relatively silent because they were aware that they had put the country in this situation. However, as soon as the economic threat was averted, they bounced back and demanded that the government must spend more. They wanted the bureaucracy to expand once again. They wanted a regular and uninterrupted increase in their salaries and allowances. Joshi made a very interesting and pertinent argument when he said that these workers never utilized their superior position and economic standing to organize the unorganized workers or peasants. They used the trade unions to retain old economic benefits and acquire new privileges for themselves. Such workers have no right to talk about the (rich) legacy of workers’ movements, claimed Sharad Joshi.

Sharad Joshi warned against the increasing government expenditure mainly on public sector enterprises that plundered consumers and created hurdles for those who wanted to increase productivity. He believed that unless the institutions can hire the efficient and fire the inefficient, this country is destined to see doomsday.

Sharad Joshi further commented that the members of trade unions carrying out the aforesaid strike have a strong belief that calling a strike is just and constitutional. He agreed with the just nature of the individual and collective rights of workers to negotiate the terms of their work. However, he emphasized that these workers don’t have the right to dictate that their factory owners should have a monopoly to produce a particular commodity. Such a monopoly or protection can hurt the way the consumers choose to live their lives and the workers don’t have a right to benefit financially at the cost of the rights of consumers. If the workers have a right to negotiate, the consumers have a right to choose, claimed Joshi. Gone are the days when the workers enjoyed all rights and the consumer had none.

If the workers claim that they can protest by calling strikes, the industrialists should have a right to decrease, increase or even cease the operations of a factory. The workers do have rights but their rights will be called just and fair only if they recognize the freedom of consumers, businessmen and industrialists to exercise their respective rights.

No wonder Sharad Joshi’s challenge fell on deaf ears. Neither the government nor the government employees took it upon themselves to prove Sharad Joshi wrong. He made it a point to draw an example of the state of affairs in the country marked by blatant heedlessness of the government by saying “…this is what happens to the real owner (the common people of India) when the servants (the government bureaucracy and the political class) become the owners.”

(The author has highlighted the key arguments of Sharad Anantrao Joshi from the ninth article – Khuli Vyavastha ani Sampa of his book Khulya Vyavasthekade Khulya Manane.)