The following is an excerpt from the book ‘History of the World’ written by John Clark Ridpath. It was republished in the Indian Libertarian magazine on October 15, 1962. In this piece, the author puts forward some compelling arguments on the threat posed to freedom by the State and Society.

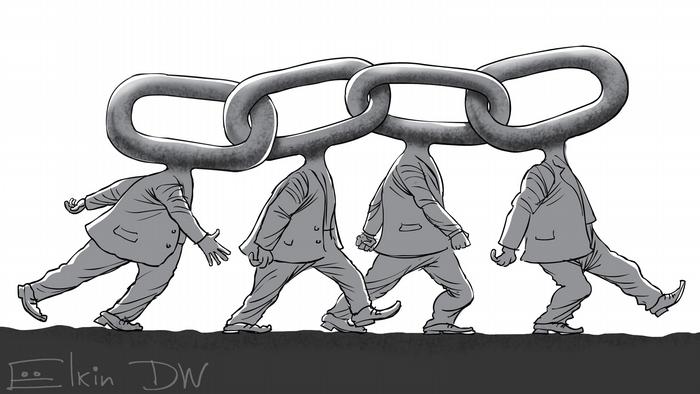

One of the greatest enemies of freedom, and therefore of progress and happiness of our race is over-organisation. Mankind has been organised to death. The social, political, and ecclesiastical forms which have been instituted have become so hard and cold and obdurate that the life, the emotion, the soul within, has been well-nigh extinguished.

Among all the civil, political and churchly institutions of the world, it would be difficult today to select that one which is not a large measure conducted in the interest of the beneficiaries. The Organisation has become the principal thing and the Man only a secondary consideration. It must be served and obeyed. He may be despised and neglected. It must be consulted, honoured, feared, crowned with flowers, starred and studded with gold. He may be left a starving pauper, homeless, friendless, childless, shivering in mildewed tatters, a scavenger and a beggar at the doorway of the court.

All this must presently be reversed. Organisation is not the principal thing; man himself is better. The institution, the party, the crowd, the government – that does not serve him; does not conduce to his interests, progress and enlightenment; is not only a piece of superfluous rubbish on the stage of civilization, but a real stumbling block, a positive clog and detriment to the welfare and best hopes of mankind.

Closely allied with this over-wrought organisation of society is the pernicious theory of paternalism –that delusive, medieval, doctrine, which proposes to effect the social and individual elevation of man by “protecting,” and therefore, subduing him. The theory is that man is a sort of half-infant, half imbecile, who must be led along and guarded as one would lead and guard a foolish and impertinent child. It is believed and taught that men seek not their own best interests; that they are natural enemies and destroyers of their own peace; that human energy when liberated and no longer guided by the factitious machinery of society and the state, either slides rapidly backward into barbarism or rushes forward to only to stumble and fall headlong by its own audacity.

Therefore, society must be a good master, a garrulous old nurse to her children. She must take care of them; teach them what to do; lead them by the swaddling bang; coax them into feeble and well regulated activity; feed them on her inspired porridge with the antiquated spoons of her superstitions. The State must strengthen her apparatus, improve her machinery. She must put her subjects down; she must keep them down. She must keep them to be tame and tactable; to go at her will; to rise, to halt, to sit, to sleep, to wake at her bidding; to be humble and meek. And all this with the belief that men so subordinated and put down can be, should be, ought to be, great and happy. They are so well cared for, so happily governed!

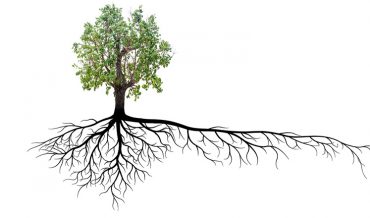

On the contrary, if history has proved any one thing, it is this: Man when least governed is greatest. When his heart, his brain, his limbs are unbound, he straightaway begins to flourish, to triumph, to be glorious. Then indeed he sends up the green and blossoming trees of his ambition. Then indeed, he flings out both hands to grasp the skyline and the stars. Then indeed, he feels no longer a need for the mastery of society; no longer a want for some guardian and intermeddling state to inspire and direct his energies. He grows in freedom. His philanthropy expands; his nature rises to a noble stature; he springs forward to grasp the grand substance, the shadow of which he has seen in dreams. He is happy. He feels himself released from the dominion of an artificial scheme which has been used for long ages for the subjugation of his fathers and himself. What men want, what they need, what they hunger for, what they will one day have the courage to demand and take is less organic government – not more; a freer manhood and fewer shackles; a more cordial liberty, a lighter fetter of form and a more spontaneous virtue.

(The above is an excerpt from the concluding portion of the book ‘History of the World’ written by one of the greatest American Historians – John Clark Ridpath. Though he wrote it 70 years ago, it could have been written today with equal force and truth)