The Muslim Satyashodhak Mandal believed that the sanctimonious people from all major religions in India have escaped from accepting modern secularism in its truest sense and have resorted to a fraudulent term called ‘Sarvadharma samabhav’.

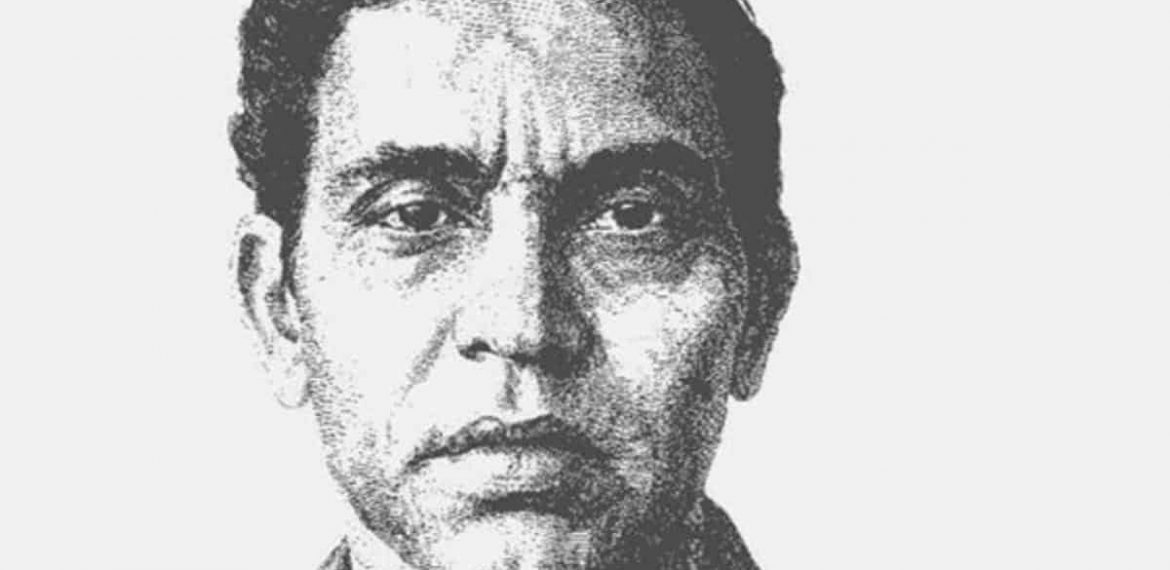

In order to explain the true nature of communalism in India, Hamid Dalwai – a Marathi social reformer drew a parallel between India and Europe in his book Rashtriya Ekatmata ani Bharatiya Musalman. He takes us back to the times when Arabs invaded Europe through Gibraltar in A.D 711. Arabs reached Tours (France) by A.D 732, in 21 years. After reaching Tours they steadily met with defeat and their campaign lost its steam. The Christians initiated a pushback, however, this process of winning back – Reconquista, took a long time. This process was over with the fall of Granada in 1492. This process of the Arab invasion and the Christian Reconquista indicates a complete cycle in the medieval history of Europe. The accounts of these invasions, conversions and even Christian inquisitions are well documented by European scholars.

Hamid Dalwai argued that a similar process started in India when Mohammad Kasim invaded Sindh in A.D. 711. Interestingly enough, according to Dalwai, India’s communal problems exist because the aforesaid cycle that occurred in Europe did not take its full course in India. Therefore, a sense of disappointment engulfed the radical sections of the Muslim community for they couldn’t fully Islamize India and because they had to lose the power to the British. On the other hand, many Hindus regret their inability to salvage the situation the way Christians successfully did in Spain. (Dalwai, 2012, p. 26) Hindus not only couldn’t turn the tide but they also had to settle with a partition. In Dalwai’s words, ‘India couldn’t become Spain but she did not become Afghanistan either’. The historic conflict has led us to deadlock and the inability to resolve it has been a characteristic of late 19th and early 20th century India. This communal deadlock has also shaped the politics, history and geography of modern India and has left deep impressions on the thought processes of the two major communities in the subcontinent.

Indian Muslims after Independence

The partition of India rendered the Muslims in India politically more vulnerable. (Kazi, 1996) In the face of uncertainty and insecurity, Indian Muslims responded in two major ways. Some traditionalists looked at the modern Indian Constitution as a Mahida between Hindus and Muslims. Mahida refers to the contract that extended concessions to the religious minorities in the form of religious liberties and guarantees of non-intervention on the part of the state. But Dalwai argued that the same section that demanded religious autonomy also demanded government jobs in proportion to their numerical strength. (Dalwai, Swatantryottar Kalatil Muslim Rajakaran, 1996) This philosophy was dependent on a two-fold strategy of stating equal claims on national resources and at the same time refuting the superiority of political authority of the state over the religious authority. Unfortunately, the prime political parties in India exploited the insecurities and flirted with these retrograde sections.

On the other hand, there were social reformers like Dalwai and progressive organizations like the Muslim Satyashodhak Mandal (henceforth Mandal) who could see the regressive nature of the demands of the orthodoxy. They envisaged a truly secular nationalism based on equality. Therefore, the Mandal took an unequivocal stance against the demands for religious autonomy which they thought were akin to the Muslim League’s demands before independence.

After the partition, forging a secular compact among people (not communities) and secular institutions was perhaps our best chance at containing communal tensions and starting afresh by shedding the burden of history. The challenge was to create a society devoid of caste and religious discrimination. Working for the upliftment of women was indispensable. Jawaharlal Nehru’s government introduced and passed the Hindu Code Bill in 1955-56, defying the Hindu orthodoxy; however, his government couldn’t reform the unjust laws affecting Muslim women. Nehru clarified his intentions of introducing a uniform civil law applicable to both Hindus and Muslim in the future as soon as the community was amicable to such an idea. (Muslimancha Anunay, 2017) The Mandal was convinced that a Uniform Family Code is the only way to safeguard the women and their equal rights, to reform the community and impart a sense of national unity based on equal citizenship. Their support had a firm philosophical grounding in the modern principles of liberty, equality and most importantly the superiority of political authority as against religious authority. To understand what they stood for, we must look at what they stood up against.

Muslim Orthodoxy Deciphered

In its publication, the Mandal highlighted some problems with the psyche of the orthodox Muslims in India. In their observation, the Muslims who opposed the Uniform Civil Code had not developed the attitude necessary for living in a modern democracy. It was so because some still relished in the nostalgia of the medieval era when India was under Islamic dominance. According to the Mandal, many of them were yet to reconcile with the modern democratic institutions based on secular principles. (Saman Nagari Kayda, 2017, p. 32) The apprehensions of Muslims about Hindu collectivism and dominance under the democratic system were valid. But there were no signs of Muslim organizations arguing in favour of liberal constitutionalism which expects both the constitution and the state apparatus to be subjected to the principle of rule of law.

The Mandal pointed out when the Islamic countries enacted new laws based on reformist interpretations that were suitable for modern times. These legislations were introduced by making changes to Sharia. But the orthodoxy didn’t want the Indian parliament to enact laws even if they were in the best interest of Muslims. Some stretched it so far as to argue that Sharia is divine and thus sacrosanct. Going by this logic, no person or political authority including the ones in the Islamic world had the sanction to change the Islamic law.

Another group among the traditionalists argued that the Indian constitution granted rights to the minorities to protect their language, culture, and religious identity; they further added that the Indian Constitution recognizes and protects the personal laws that originate from Sharia. That is exactly why personal laws cannot be tempered. They questioned the sovereignty of the Indian parliament and upheld the religious laws as superior. (Saman Nagari Kayda, 2017) The attempt to alter these laws, according to them, would be tantamount to violation of the Indian Constitution. This attempt of using the constitution as the shield was seen as unfortunate by the Mandal. These socio-religious constructs and the notion of the infallibility of religious scriptures made Muslims too sensitive to have any reasonable discussion, change or reform, claimed the Mandal in its publication. (Dharmanirapekshata, 1996, p. 56)

Limiting Religion to the Private Sphere – Concepts of Aadat and Ibaadat

The Muslim Satyashodhak Mandal opined that the State had to work towards the introduction of the Uniform Civil Code. They outrightly rejected the argument that Sharia is a divine law created by God. They reasoned that the concept of religion encompasses two core ideas – namely, ‘Aadat’ and ‘Ibaadat’. Aadat deals with temporal affairs or the world that we live in. The other concept of Ibaadat is concerned with all that is spiritual. This broad distinction lies in the fact that what falls under Aadat is amendable, whereas the other part – Ibaadat should be protected by the state. However, most fatwas issued by the clergy deal with daily life and worldly matters.

Laws that govern our lives are always made by society or people. Thus, Mandal believed that laws cannot be associated with the divine and the authority to govern the society must remain with the state and not with any religious institution. The Mandal was certain that where worldly affairs are segregated from the spiritual life, the religious liberties can remain relatively untouched. Rather the Mandal argued that the worldly aspects enshrined in any religious scripture must change as per the changing requirements of the society. The possibility to amend the way of life is what brings the much-needed flexibility that can in turn help us protect the cherished tenets and values of our respective religions. (Saman Nagari Kayda, 2017, p. 35) While the Mandal favoured managing worldly matters at the hands of the political authority, curtailing the pervasiveness of the religion, it also had a stated objective of destroying the clergy’s monopoly.

Based on the aforesaid arguments and based on the philosophy of the Preamble to the Indian constitution, the Mandal believed that article 44 directs the State to work towards legislating to bring about social welfare and reform. However, only the power to legislate doesn’t suffice. These laws will fall short of achieving their stated objective if the mental make-up of people does not change. (Mukadam, 1996)

Plea for Secularism, not Sarvadharma-Samabhav

The Muslim Satyashodhak Mandal believed that the sanctimonious people from all major religions in India have escaped from accepting modern secularism in its truest sense and have resorted to a fraudulent term called ‘Sarvadharma samabhav’. India is a country with multiple cultures, religions, sects and innumerable castes. There are religions, sects and castes that have contradictory traditions and customs. How can they all practice their customs together at the same time? How can a mongoose and a snake dwell in the same house? If neither wants to die, the only solution would be to make them both change their nature. Sarvadharma samabhav cannot achieve that. Because the term implies that if a particular religious institution is supported by the state, a similar concession is also to be extended to the institutions of other denominations. This will eventually culminate in a competition between religions. Which demands will the state fulfil? How far can it make concessions and favours to the religious denominations? And a more fundamental question is, what are the functions of the state? Why was the state created in the first place? It would defeat the whole purpose of the state if it degenerates into machinery stimulating religious institutions and (unduly) protecting religions.

Mandal firmly believed that only Secularism can help us. It drives religion out of the public sphere but it protects religion in private life. Secularism recognizes the right to practice any religion, any way of worship so far as it is contained in the private sphere. It does not support or promote religion. Secularism also stands for the recognition of the right to not believe in any religion.

The question persists, as to why we should read the works of Hamid Dalwai or the works of members of the Muslim Satyashodhak Mandal? They were social reformers whose economic ideas were more or less in tandem with the social democrats in the Congress or the Socialist Party. However, their political and social ideas were rooted in individualism. “India [Indian Constitution] has put restrictions that prompt the society to take the path of secularism. The religious liberties have been bestowed upon the individual, not religions.” (Dharmanirapekshata, 1996, p. 57).

The works of Hamid Dalwai and the Muslim Satyashodhak Mandal have been consciously written in a regional language and without any jargon of the academic language. The main reason behind such a practice is the firm belief in making the public politically informed, with the hope that if the citizens have an informed opinion, they are less likely to be swayed by the rhetorics of the political elites and the clergy. These works have a greater value than just being one more addition to many political ideas because they aim at releasing the citizens from being held emotionally hostage by people in power.