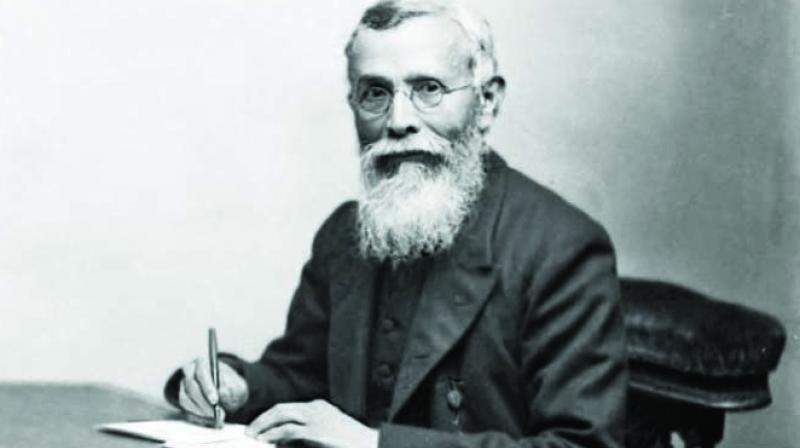

In his decades-long career in Britain, Naoroji laboured relentlessly to popularise the Indian cause. Given the uncooperative attitudes of colonial bureaucracy at home, Naoroji figured that the best way to serve Indian interests would be to influence decision-making in the British parliament. (Image Credits : The Asian Age)

The early phase of nationalist movement in India, dominated by the largely liberal-minded moderate faction of the Indian National Congress (INC), saw them envision a wholesome agenda for the regeneration of India.

Prior to creating an Indian political subject, these liberal leaders were invested in the project of creating an Indian public sphere. The eventual culmination of the liberal political project lay in achieving self-rule- interpreted differently as political independence or dominion status- by constitutional means. The vision of modernisation wasn’t limited only to the political realm as Indian liberals also sought to reform the society deeply anchored in orthodoxy.

The native Indian modernisation project under the colonial tutelage, though, had to contend with both the obstructive and accelerating tendencies of the imperial metropole. The career of Dadabhai Naoroji, the Grand Old Man of Indian nationalism and perhaps the most prominent liberal figure, captured the zeitgeist of this early phase of Indian nationalism.

Even as liberals were first challenged by the ascendant Congress extremists and were later completely side-lined during the mass nationalism phase under Gandhi, their vision and ideas were co-opted by the later generation of Indian nationalist leaders, as shown by the late CA Bayly. In that sense, Indian liberalism remained foundational to the idea(s) of India even if in adopted fashion and as such merits scholarly attention.

In pursuit of their agenda for social reform, political rights, and economic regeneration, Indian liberals, including Naoroji, employed a variety of measures. These included educational enterprise, creation of a reading public sphere, formation of political associations, petitions to the Raj administration, counter-preaching, historicism, turning of the defence witnesses, and both upward & downward hermeneutics. Naoroji’s career was emblematic of this liberal phase of Indian nationalism, in both his ideas and methods, which shall be explored below.

Naoroji as Social Reformer

Given the challenges of regressive social practices, religious orthodoxy, repressive colonialism as well as imperatives of the democratic polity, the need to create a civil society beyond the tyrannies of state was evident to Indian liberals. Gopal Krishna Gokhale’s Servants of India society, Mahadev Govind Ranade’s Deccan Sabha, and Poona Sarvajanik Sabha were some notable associations, which sprang up to represent Indian interests and demand rights from the state. Mass illiteracy, however, posed a challenge to the broadening of civil society as well as the promulgation of rational discourse. Indian liberals thus turned to educational initiatives to foster mass literacy. The pedagogical element of the social reform agenda of liberals was concerned with both mass education and female literacy.

Himself a beneficiary of benevolent scholarships, Naoroji was an ardent advocate of free education for masses. In his Bombay stint as an academic in the mid-1800s, he belonged to the Young Bombay clique of social reformers and educationists. As historian Dinyar Patel has argued convincingly, in contrast to Kolkata, the Bombay-based native Indian elites exercised considerable agency in the education sector as instructors and financiers. It was the alliance between progressive intellectuals and rich shetias (mercantile community) that fostered the social reform agenda of the Young Bombay.

With its belief in the intrinsic value of the western liberal education, the Young Bombay group deployed education in service of social reforms and modernisation to create the liberal political subject in India. Naoroji was instrumental in shaping the educational reform agenda along with fellow western-educated, liberal-minded reformers- Navrozji Fardunji, Karsondas Mulji, Bhau Daji, Ardeshir Framji Moos and Behramji Malabari. The most enduring contribution of Naoroji came in the form of creating an enduring institutional base for liberal values in the domain of pedagogy.

The initiatives undertaken included Parsi Lehak Mandli where he was the founding member and first editor; the Parsi Natak Mandli where he was a co-founder; and the Framji Cowasji Institute where he was instrumental in raising funds. At Elphinstone’s College where he was teaching, Naoroji founded the Students’ Literary and Scientific Society (SLSS) in 1848. Three months later, SLSS was followed by the Dnyan Prasarak Mandli (Society for the Diffusion of Knowledge) as a branch of the SLSS, which produced content in Gujarati and Marathi language.

Part of the initiative also included the promotion of female education. Naoroji’s reformist zeal for gender equality spurred his endeavour. In October 1849, he would go on to open six schools for girls under the banner of the SLSS. Again, the progressive shetias came to provide the financial ballast. The donors included Jagannath Shankarsheth, Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy, Framji Cowasji Banaji, and Cowasji Jehangir Readymoney.

The ambit of reforms went beyond social issues to rationalise religious practices deemed irrational. The initiative was partly an insider response to critical charges from Christian missionaries and partly a bid to create the liberal political subject through character building. Naoroji’s religious reforms were mostly focused on his own Parsi community. In this initiative, his partner was the haltingly English-speaking but reform-minded shetia, Kharshedji Nasarvanji Cama. Apart from widening the distribution of the Dnyan Prasarak Mandli’s publications, Cama was involved with Naoroji in two other reformist enterprises that riled the Parsi orthodoxy.

In 1851, Naoroji and colleagues founded the Rahnumae Mazdayasnan Sabha (Society of the Guides of the Mazdayasnan Path) and Rast Goftar, a newspaper in Gujarati. According to Dinyar Patel, the Sabha went on ‘protestantising aspects of Zoroastrianism by removing supposedly foreign and inauthentic customs and practices.’ Reformist in its orientation, Rast Goftar took a slew of causes, including the discontinuance of child marriages, the inappropriateness of nautches, and the rights of women in adopting European clothing.

However, as Dinyar Patel points out, Naoroji succumbed to oriental stereotypes in his bid to reform Parsi tradition. Naoroji’s excuse for certain ‘irrational’ Parsi practices lay in attributing it to corruption borrowed from Hindu and Muslim traditions. In later years, the involvement of Karsandas Mulji increased the scope of the Rast. Meanwhile, Naoroji would go on to broaden the scope of both issues that he espoused and places that he went in advancing India’s interests.

Advancing Indian Causes in the Transnational Public Sphere

Naoroji’s concern with India’s regeneration was set in the context of the globalised production system and circulation of ideas. As a man of letters and public figure in both Britain and India, Naoroji was involved in crucial conversations on matters of anti-imperialism, political economy, race, gender rights and political economy. His long stay in Britain, including a parliamentary stint as an MP, meant he was a noteworthy participant in the transnational public sphere. The transmission of ideas happened in both directions, best captured in Bayly’s conception of upward and downward hermeneutics. Naoroji made references to international events in his writings, formed alliances with a variety of political actors abroad, and influenced public debates in Britain and other countries.

For example, his formulation of the ‘drain of wealth’ theory deployed international statistical comparisons to hammer his point on India’s persistent impoverishment home. In “The Wants and Means of India”, he drew the balance of trade comparisons with the US, Australia, and Canada. By the mid-1870s, he turned to study the US economic experience and initiated correspondence with the US state officials in the Army Corps of Engineers and various state departments including those from Agriculture, Treasury, and the Interior. Dinyar Patel writes that Naoroji’s correspondence with the US officials concerned with statistics collection continued in the early 1900s.

His work on the drain of wealth influenced public debates as far as Cyprus and the USA. In July 1902, Naoroji received the request for a copy of his recently published Poverty and UnBritish Rule in India from the Cyprus-based M Sevasly. Mr Sevasly wanted to analyse the impact of British rule on his country with reference to Naoroji’s work on India. In the USA, Naoroji’s arguments on the exploitative nature of imperialism were wielded by the anti-imperial Progressives. According to Dinyar Patel, it was George Freeman, a reporter for the New York Sun, who introduced Naoroji’s ideas to Edward Atkinson, the founder of the American Anti-Imperialist League and William Jennings Bryan, the leading progressive leader in the US.

In Naoroji’s description of degrading poverty under imperial rule, Freeman found support for his warnings against the US expansionism in the Pacific and Latin America. Freeman popularised Naoroji’s ideas by distributing it to political leaders, universities, public libraries and newspapers. He also convinced Naoroji to send his writings to the elected leaders in the US Senate. Though, we aren’t aware of further correspondence between Naoroji and serving senators on this matter.

In his decades-long career in Britain, Naoroji laboured relentlessly to popularise the Indian cause. Given the uncooperative attitudes of colonial bureaucracy at home, Naoroji figured that the best way to serve Indian interests would be to influence decision-making in the British parliament. To this end, he fought multiple election campaigns in Britain, twice as a Liberal Party candidate and once as an independent Liberal candidate. The active political career in Britain entailed courting different constituencies in order to win elections as well as garner support for India. Naoroji’s wide-ranging connections as a politician had a distinctly progressive and anti-imperial character.

Historian Dinyar Patel has uncovered Naoroji’s long friendship with and influence over Henry Hyndman. Among the leading members of British socialist movement, Hyndman drew heavily upon Naoroji’s drain theory in his article titled “The Bankruptcy of India”. Interestingly, as Dinyar Patel shows, Hyndman also told Karl Marx that “I want you very much to meet Mr Dadabhai Naoroji to whom I am much indebted for facts and ideas about India.”

In August 1904, both Hyndman and Naoroji attended the International Socialist Congress in Amsterdam. In the initial stage of his electoral run, Naoroji also briefly considered courting a Tory candidacy, which he discussed with Scawen Blunt. To this end, George Birdwood offered to arrange meetings with British Conservative politicians.

Dinyar Patel has argued that Naoroji mainly courted three constituencies during his stint in British politics- workers and trade unions, Irish nationalists, and the disenfranchised feminists. His alliance with feminist activists was reflected in his involvement with the feminist associations. Naoroji served as a vice president of the Women’s Progressive Society and the International Women’s Union. He was also a council member of the Women’s Franchise League.

Himself a target of vicious racist jibes from no one less than the Conservative prime minister Lord Salisbury in the infamous Black Man incident of 1888, Naoroji took an active interest in transnational initiatives against racism. He forged ties with Catherine Impey who was the founder of a journal called Anti-Caste. The journal campaigned against all forms of racial injustice and attacked both casteism in India and lynching of Blacks in the post-reconstruction American South. Remarkably, Impey also introduced Naoroji to the famous black civil rights activist, Ida B Wells. Later in 1907, WEB DuBois published excerpts from Naoroji’s radical presidential speech at the Calcutta session of the Indian National Congress (1906) in his magazine Horizon.

For all his progressive views and socialist leanings, Naoroji remained at core a member of the liberal establishment, both in India and Britain. In fact, it was his friends in Bombay, most notably AO Hume, who leveraged their connections to induct him in the British Liberal establishment of politicians, civil society associations and journalists. Not only did Naoroji fight the elections twice on the Liberal Party ticket, but he also engaged with the National Liberal Federation, London-based Liberal Central Association, Manchester-based National Reform Union, and the Holborn Liberal Association to name a few.

Statistical Liberalism and Drain of Wealth

Coined by CA Bayly, the term ‘statistical liberalism’ refers to the Indian political economy fashioned by liberals to challenge colonial appropriation and exploitation. According to Bayly, the “fundamental principle of Indian Statistical liberalism was that impoverishment and famine were not the natural outcomes of human improvidence and extravagance combined with overpopulation.” The most prominent practitioners of this version of political economy were RC Dutt, KT Telang, and Dadabhai Naoroji. Given his academic background in mathematics, Naoroji deployed statistics and empirical data to counter the official reports, which served the narrative of progress under the Raj’s ethnographic state and legitimised the colonisation project.

Naoroji was, by no means, the original proponent of the drain theory. Noted Indian liberal Raja Rammohan Roy and the little known Ramkrishna Vishwanath as well as British officials, including James Silk Buckingham, Montgomery Martin and others had broached the topic earlier in their own ways. But, Naoroji arguably was the most prominent proponent of the theory.

His statistical liberalism consisted of calculating the extent of poverty in India, identifying the causal mechanism behind the drain (council bills deployed in the salary and pension payments for British officials in the Indian civil service), vigorously promoting the solution (Indianisation of the bureaucracy as well as self-rule under the dominion status which Dinyar Patel calls the ‘political corollary’ to the drain).

Naoroji’s first public pronouncement on the matter came in 1867 with his delivery of “England’s Duties to India”. Dinyar Patel has identified two factors behind this political economy turn in Naoroji. The so-called Orissa famine of 1865-67 and the financial crisis in Bombay in the wake of the culmination of the American Civil War showed the precariousness of Indian lives and livelihoods. It was this degrading economic condition that might have drawn his attention to the matter.

In a detailed study, Dinyar Patel has identified several methods involved in Naoroji’s engagement with statistical liberalism. To begin with, Naoroji ‘made the first-ever estimates of the country’s gross income per capita (technically, gross production per capita).’ The result punctured the myth of bountiful progress under the British Raj. To further make his polemical case effective, he relied on statistical comparisons for the shock value they produced. Witness for instance his claim that the income of the average Indian peasant was less than the bare minimum living expenditure on an Indian prisoner or coolie emigrant.

The third method involved deploying the testimony of British officials to argue his case. CA Bayly argued this kind of turning of the defence witnesses ‘not only undermined the authority of the Anglo-Indians but it also neatly deflected the charge of sedition.’ The final step was criticising the veracity of official statistics on empirical grounds. This involved pointing out the obscuration of differing local conditions in the official data and relying on sources on the ground for additional information.

Naoroji’s drain theory has come under criticism from later scholars of economic history and rightly so. Even historian Bipan Chandra, who otherwise sympathetically treated economic nationalism of Congress moderates- which is understandable given his Marxist leanings- found Naoroji’s fixation with the remittances absurd. More substantial criticism has come from other scholars though.

KN Chaudhuri, for instance, calculated the drainage amounting to ‘less than 2 per cent of the value of India’s exports of commodities’ during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Others have pointed out the productive output generated in India from the so-called drain, which should be an investment. Vera Anstey argued if India had maintained its own army and navy, this arrangement might have cost more than the drain amount.

Tirthankar Roy has argued that the services purchased abroad might have spurred the growth of businesses at home. Moreover, Indian nationalists were being cynical (Roy’s words, not mine!) in calling the cost of buying the technical knowledge drain. More recently, Dinyar Patel’s defence of Naoroji has come in the form of positioning drain theory as a political polemic rooted in data and empirical observations to further the anti-imperial cause, not a neutral, objective analysis.

Of course, there is no denying the fact that the drain debate served the intended purpose of puncturing the legitimacy of the Raj. However, in so far as ideas tend to have an afterlife, the far-reaching impact of the drain formulation has been negative for the Indian economy. Naoroji and his fellow statistical liberals’ protectionist economic agenda, suspicion of foreign capital and trade, and envisioning of a larger role for the state went on to shape the economic agenda of Indian nationalists including Gandhi and resulted in the Nehruvian mixed economy.

As the economic liberalisation of 1991 has made clear, for the folly of economic nationalism, part of the onus lies on Naoroji and his fellow travellers who institutionalised such ideas in the Indian nationalist movement. And, if anyone doubts the enduring impact of Naoroji’s ideas, one only has to look at the swadeshi ideology of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and politician Shashi Tharoor’s tirade against the British Raj, which extensively quotes Dadabhai Naoroji!

Conclusion

In my opinion, the moniker that best captures the legacy and status of Indian liberal tradition is ‘forgotten’. Naoroji’s long public career in service of the nation has been no exception to this general trend. In this regard, a new biography of Dadabhai Naoroji, Naoroji: The Pioneer of Indian Nationalism, by historian Dinyar Patel might serve as a much-needed corrective though.

Author’s Note: This article draws heavily on the research of historian Dinyar Patel. The author gratefully acknowledges his contribution.