The following piece was published in the June 1959 edition of the Indian Libertarian Magazine. The author of this piece, Mr. A Ranganathan discusses the Indian Constitution vis-a-vis individual freedom in the light of amendments as well as the enactment of laws promoting Co-operative farming. The issue of property rights has been mentioned as fundamental to the relationship between the individual and the Indian Constitution.

The success of democracy does not merely depend on the eloquent words enshrined in the Constitutional Preamble. Every student of political science knows that even such a centralized State as Russia is based on a constitution which is federal in theory! In the last analysis, the Constitution is an extremely delicate mechanism which is controlled by the mainspring of liberty in creating the proper balance between public authority and individual freedom.

The Indian Constitution is at once evolutionary and revolutionary-evolutionary because India’s new constitution is patterned to a great extent on the Government of India Act of 1935, except for a few changes necessitated by the achievement of Indian Independence, and revolutionary since the Constitution is based on the republican idea, which is definitely a break with the Indian tradition of a monarchial form of government. The nineteenth century was a period of internecine struggle between democracy and monarchy ultimately resulting in the triumph of the democratic idea, which can be said to be the legacy of the twentieth century. But countries which emerged from a period of political domination (there have been exceptions in European history) generally plumped for a republican form of government. The adoption of the republican idea is therefore a product of the forces of history.

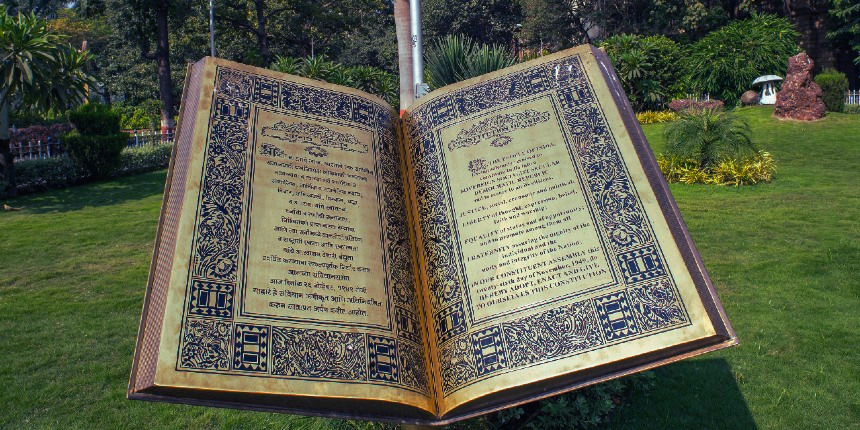

THE PREAMBLE

The preamble, eloquently enough wishes to secure: ‘JUSTICE, social, economic and political. ‘LIBERTY’ of thought, expression, belief, faith and worship. ‘EQUALITY’ of status and of opportunity and to promote among them all ‘FRATERNITY’ assuring the dignity of the individual and the unity of the Nation.

The Indian Constitution is different from the previous ones in many respects. Nearly five hundred States which formed ‘NATIVE INDIA’ vanished from the scene. While the old dichotomy between ‘British India’ and ‘Native States’ had been removed, a new classification was introduced – part A states, part B states; and so on. The old princes were made to fit in with the new constitutional pattern, because clad in pseudo-purple and designated as Rajpramukhs who have been abolished. Another important feature of the Constitution is adult suffrage which confers the status of a voter to every man and every woman who is a citizen of India and who is not less than twenty-one years. Perhaps the most Important feature of our new constitution is the section on Fundamental Rights.

CURBING INDIVIDUAL RIGHTS

Any discussion of a constitution must necessarily take into consideration the various amendments which take place from time to time. It is well known that changes, both economic and technological, promote the tendency towards centralization. In this connection it is interesting to recall the great role played by the American Supreme Court in fashioning a legal apparatus which was responsible in adopting the American Constitution, framed for a predominantly agricultural country with a few million people, to the ever growing needs of a great industrial power with more than thirty times the original population. The justification for a judicial interpretation of a constitution finds its expression in the historic words of Chief Justice Marshall who declared: “It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the Law is.” And if a comparative study of the various amendments of the American Constitution and the amendments effected in the Indian Constitution is made, one can easily arrive at the conclusion that the scope of individual rights has been broadened in US whereas the area of individual freedom in India is being steadily narrowed.

EXECUTIVE POWER INCREASED

Since Indian Independence, there has been a sustained effort to increase the powers of the Executive at the expense of the courts. Pandit Nehru has violently opposed the idea of the Supreme Court being the final arbiter on the quantum of compensation on the plea that the Supreme Court ought not to make itself a third chamber of legislature. It would be difficult to deny that this amendment which vested this power in parliament has made great inroads into the domain of the individual. This new power of fixing the amount of compensation is theoretically vested in parliament but in actual practice will have to be delegated to the ruling party and finally administered by the Executive officers. And it becomes all the more serious when the Government proposes to introduce Co-operative Farming.

In a recent lecture Mr. V. P. Menon has said that the policy of fixation of ceilings raises the question of right to property – “In contrast to the Zamindaris, the land to which the ceiling applied was purchased in the market out of honest savings and these land Reform Bills, would be the means for expropriation of private property.” Indeed, there can be no doubt that cooperative farming on a nation-wide scale which is sought to be implemented by the nostrum-fed planners will do violence to the individual’s freedom of action guaranteed by the Constitution. Another proposal of a serious nature is to set up administrative tribunals in different states on behalf of the Central Government to pronounce the final verdict on revenue disputes and also matters pertaining to Government employees. This measure, if brought into force, will prevent High Courts from discharging their normal functions. On the one hand we are assured of Fundamental Rights and on the other hand, everything is taken away in the name of social “progress and freedom.” The Court is the last resort of the aggrieved citizen and if he is deprived of this right, it simply means the negation of democracy. This proposal is most surprising, if we reflect on the statements of Congress leaders who had asked for a separation of the judiciary from the executive during the British regime. The idea of instituting administrative tribunals is to take over the functions of the Judiciary by the Executive. The serious implications of this proposal can be grasped if we examine it in the light of various measures – Preventive Detention Act, Wealth Tax, Expenditure Tax, the Essential Services Maintenance Bill, all leading to an over-centralized bureaucracy contributing to an atmosphere of a police state.

THE NECESSARY AMENDMENT

Our Constitution as it is needs only one amendment. The time limit for the use of English in our day-to-day administration must be extended by a further period of twenty-five years, if not more. The most important thing at the moment is to make the Government take suitable steps to amend the Constitution to include English as one of the languages mentioned in the Eighth Schedule. The next step would be to delete Part XVII of the Constitution. Indeed, even article 315 of the Constitution has made it clear that Hindi is still an undeveloped language and it is difficult to understand the reason behind the idea of imposing Hindi, when English serves our purposes admirably. Again Article 344 (3) says that in making their recommendations, the (official language) commission shall have due regard to the industrial, cultural and scientific advancement of India and the just claims and the interests of persons belonging to the non-Hindi-speaking areas in regard to the public services. Mr. P. Medapa, says foreign language is legally untenable and constitutionally incorrect. It is well to remember in this connection that the Bombay High Court had shown that English is not a foreign language in pronouncing judgement on the celebrated Bombay School case.

Previous musing: IS SOCIALISM OUTDATED?