To stem the flood of imports that this regime might otherwise allow, the system has been bolstered in several other ways. Imports can be brought in only by an “actual user”; in other words, intermediaries are banned. As part of the domestic capacity licensing scheme, firms can be obliged to sign up for a “phased manufacturing programme”: they are allowed to expand their factories, but only if they promise to reduce the import content of the goods they produce.

In continuation with last week’s musing, produced below is an extract from the second part of The Economist’s coverage of the political economy of India in wake of the 1991 economic crisis. The article was re-published in the October 1991 issue of Freedom First, a liberal magazine established by Minoo Masani.

In the last issue of Freedom First, we had published extensive extracts from the Economic Survey of India (May 4, 1991). The comprehensive survey written in easy to understand English needs to be read by as many Indians as possible – particularly those being misguided by vested interests into opposing Dr Manmohan Singh’s reforms. The vested interests oppose the freeing of the economy for they will no longer have the protection of the state to keep their sinecures and continue making a fast buck at the expense of the people of India.

While the reformists need our full support, we are unable to appreciate their plea that no purpose will be served discussing the past four decades.

We must know what went wrong and why – to avoid such mistakes. Hence we at Freedom First decided we should share with you the rest of the ‘Survey of India’. The first post discussed the ‘cage’ in general. The second dissects the nature of the cage and what needs to be done to enable the Indian tiger spring the cage.

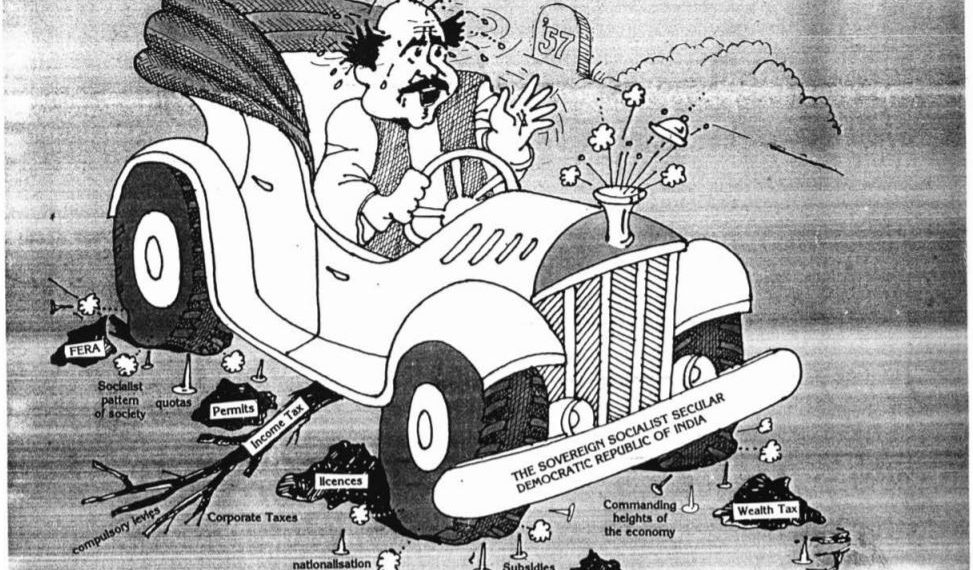

Plain tales of the licence raj

India has one of the most protected domestic economies in the world. The guiding principle has been to allow imports only when necessary. Bureaucrats make that judgment largely case-by-case.

To stem the flood of imports that this regime might otherwise allow, the system has been bolstered in several other ways. Imports can be brought in only by an “actual user”; in other words, intermediaries are banned. As part of the domestic capacity licensing scheme, firms can be obliged to sign up for a “phased manufacturing programme”: they are allowed to expand their factories, but only if they promise to reduce the import content of the goods they produce. An entirely separate set of procedures is used to monitor imports slated for a reduction under these programmes. Then there are 16 “canalising agencies”, government bodies that are granted a monopoly of certain imports: oil, steel, rubber, newsprint and so on. Finally, to be on the safe side, there are tariffs – which are the highest in the world.

To complete India’s isolation from the world economy, the government has discouraged inward flows of know-how and capital. Despite some recent liberalisation, there are limits on the fees that Indian producers can pay for the use or purchase of foreign technology; technology imports may be banned if the import content of the production process is deemed too high. The Foreign Exchange Regulation Act of 1973 keeps a tight control on inward investment. Most foreign companies have been obliged to reduce their equity holdings to a maximum of 40%. The others are more tightly regulated than equivalent Indian firms.

The full text could be accessed here.

IndianLiberals.in is an online library of all Indian liberal writings, lectures and other materials in English and other Indian regional languages. The material that has been collected so far contains liberal commentary dating from the early 19th century till the present. The portal helps preserve an often unknown but very rich Indian liberal tradition and explain the relevance of the writings in today’s context.

Read more: SO Musings.