The following excerpt has been taken from the Occasional Paper titled ‘Globalisation and the Poor’ written by Johan Norberg. The paper is based on a contribution of the author to the workshop Campaigning for Free Trade; organised by the Liberal Institute of the Friedrich Naumann Foundation in November 2003.

The anti-globalisation movement had its coming-out party in Seattle in 1999, when thousands of activists and trade union members protested against a new round of trade negotiations in the World Trade Organisation. Millions were drawn to these protests because of a preceding anti-WTO statement that was circulated on the internet, and signed by about 1500 different groups, from churches to militant communists. Their first accusation against the WTO in the statement was that free trade and globalisation:

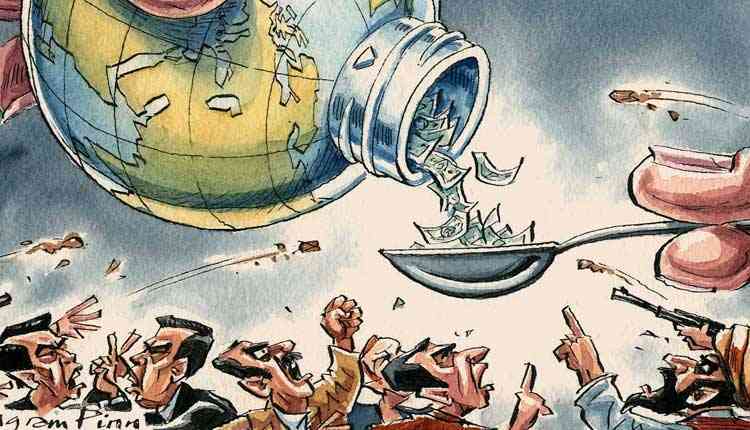

“…has contributed to the concentration of wealth in the hands of the rich few; increasing poverty for the majority of the world’s population; and unsustainable patterns of production and consumption.”

Poverty is also a major issue when you read anti-globalist writers and theoreticians. Their view is that globalisation is making the rich richer and the poor poorer. If this is their biggest concern, surely they should change their mind about the globalisation process if they got new information, which not merely shows that globalisation is not increasing poverty, but in fact an efficient way of reducing human poverty. That is what I am going to argue for in this paper, and I will also present the current debate on poverty measurements. What has happened to poverty in the era of globalisation, and why?

Relative or absolute?

To begin with, we must define what we mean when we discuss poverty. Most often there is a discussion whether absolute or relative poverty is the most relevant measurement. In this debate, I am an absolutist. Relative poverty is not a measure of poverty, but of inequality. Instead of measuring how poor someone is, it says how poor that person is in relation to others. One poverty concept frequently used, e.g. by the UNDP, rates a person as poor if they have less than half the median wage in the country where they live. This means that a person regarded as ‘loaded’ when living in a poor country like Nepal is considered as poor as a church mouse when living in the affluent USA. These relative figures, consequently, cannot be compared internationally.

But the biggest problem with the relative concept is that it completely distorts our view of poverty. Poverty in China has been reduced faster than ever in the last two decades. People have higher wages and better living standards than ever before. But at the same time income gaps within China have widened because towns and cities have grown faster than the countryside. Inequality has grown, and therefore, relative poverty has grown, even though everybody is richer than before. Surely there must be something wrong with a measure that says that poverty is increasing when everybody gets richer? Only those who consider wealth a greater problem than poverty can find a problem in some millionaires becoming billionaires while others get out of poverty.

An absolute poverty concept is to be preferred, for example a specific money line. But that view has also been challenged. As Amartya Sen, Indian economist and Nobel laureate, has emphasised, poverty is not just a material problem. Poverty is something wider, it is about powerlessness, about being deprived of basic opportunities and freedom of choice. Small incomes are often symptomatic of the absence of these things, of people being subjected to coercion and marginalisation. Human development. means leading a reasonably healthy and secure life, with a good standard of living and freedom to shape one’s own life.

But even though I accept this criticism to a big extent, the investigation of material development is important. Both because it indicates how these conditions have developed and also because it contributes to development as such. It is material resources, individual and societal, which enable people to feed themselves, be educated, obtain health care and be spared watching their children die. It can and should be combined with other indicators of human welfare, but it is one of the most important ones in itself.

The most common international poverty line is the World Bank’s definition of absolute poverty. According to this definition you are poor if your income is less than one dollar a day, to be exact, $1.08. And this is adjusted for purchasing power, so that it corresponds to the same standard in all countries. This definition was chosen because it was the median of the poverty definitions in the ten poorest countries that the World Bank had detailed statistics from. And probably also because it is easy to popularise and remember. Let’s use that definition to dig into the historical change in poverty rates.

The extent of poverty

In 1820, about 85 percent of the world population lived on the equivalent of a dollar a day, converted to today’s purchasing power. The biggest misconception in the debate on globalisation is that poverty is supposedly something new, and that things are getting worse. It is not. One hundred years ago, every country was a developing country. The new thing in our modern world is not poverty, but wealth. The fact that some countries and regions have escaped that poverty.

In the beginning of the 19th century something happened and poverty began to decline. In 1910 only 65 per cent lived in absolute poverty and in 1950 55 percent. Then came another big change. UNDP, the United Nations Development Programme, has observed that, all in all, world poverty has fallen more during the past 50 years than during the preceding 500. In 1970 absolute poverty had shrunk to 35 per cent, in 1980 it was slightly more than 30 per cent, and today it is about 20 per cent. (Often the figure 23 per cent is mentioned, but that is as a proportion of the developing country population.)

Even though the proportion of people in poverty has been shrinking in the last 200 years, the number of poor has increased, because the world population has been increasing constantly. Unique with the decline in the last twenty years is that not only the proportion, but also the absolute number of absolute poor has declined – for the first time in world history. During these two decades, the world population has grown by about 1.8 billion, but yet the number of absolute poor has declined by about 200 million people, according to the World Bank. Material developments in the past half-century have resulted in the world having over three billion more people liberated from poverty.

Read the complete paper here.